Reflections and Collections for the 21st Century Social Studies Classroom

Nineteen years ago, I wrote my high school senior research paper on the conservatism of the American Revolution. I used primary sources to argue, quite cogently for an 18-year-old, that the "American Revolution was a conservative movement aimed at restoring traditional British rights to the American colonists." Apparently, I was relying heavily on Daniel Boorstin and had not read much of Gordon Wood or Bernard Bailyn in high school. So, was the American Revolution radical or conservative? The American Revolutionaries' fight for liberty began as a conservative argument for rights as British subjects. However, the more radical nature of the American Revolution is evident when we look beneath the surface at the new argument Americans used to defend their rights: the higher-law principles of consent of the governed and natural rights. This radicalism, however, was tempered by the failure of the American founders to extend political rights to all those who naturally deserved them. For the British, sovereignty resided with the "King in Parliament." The British government was a hybrid system with medieval elements of a hereditary monarchy and House of Lords. But, it also included a House of Commons, and system of rotten burroughs in which representation was not proportional to population. Although radical Whigs in Britain began to assert the doctrine of consent, most Whigs and Tories had to agree not to address any such principles of higher law because it would require their entire system to be reworked. They agreed to ignore the problem of consent and pretend the Glorious Revolution was just a moment of inconvenience. As Americans agitated for their rights, the British continued to defend their system only on the grounds of customs and traditions of British law. In the "Summary of the View of Rights of British Americans," Thomas Jefferson tried to force the British to deal with the higher-order issue of consent. He blamed the King for failing to act as a negative against Parliament. Jefferson argued that colonial legislatures had equal authority with Parliament and it was the responsibility of the King to use his negative to protect the American colonies. But, of course, there was no such tradition that would allow these kinds of checks. It was only on the basis of higher-law principles of consent that the King could act in such a manner, and the British would not concede a higher law. Edmund Burke recognized the problems inherent in British taxation of the American colonies. He argued that the British government should stop taxing the Americans because it would continue to raise questions about higher-law principles and point out contradictions in the British system. Nonetheless, the British continued to assert the right, through the Declaratory Act, to do as they wished because Parliament was supreme. The Declaration of Independence was the Americans' magnum opus on higher-law rights. The Declaration listed grievances against the King for violations of the rights of colonists, but only after asserting a radical idea for the origins of rights: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness." While the ideals of the Declaration and American Revolution were radical, the political realities were far from matching the rhetoric. Although some states outlawed slavery during and immediately after the American Revolution, the Constitution left in place a system of slavery that denied the most basic natural rights to enslaved African Americans. Frederick Douglass pointed out these contradictions in his 1852 speech, "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?": "Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! ...The blessings in which you this day rejoice are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity, and independence bequeathed by your fathers is shared by you, not by me. ...This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. ..." Abolitionists of the 19th century (along with later women's rights and civil rights leaders) understood that the higher-law principles of the Declaration were the true foundation of freedom and equality. Setting out the aims of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1833, William Garrison called liberty both an inalienable right and a God-given right. To deny another liberty, he reasoned, infringed upon both the “law of nature” and constituted a “presumptuous transgression of all the holy commandments.” He concluded the same manifesto by affirming the movement’s two foundational documents: The Declaration of Independence and the Bible. Garrison was critical of the Constitution for its concessions to slavery, especially the Three-Fifths compromise. He regarded this as a betrayal of both republicanism and Christianity. The Declaration of Independence asserted the high and radical aims of the American Revolution: the Enlightenment principles of consent of the governed and natural rights. But forces of conservatism kept many from enjoying those rights until later generations of radicals led movements for political change.  Rather than recommending a specific bibliography of works worth reading, I find it easier to recommend historians and social studies educators whose works I have found useful. This is especially true in recent years, as "works" are often in the form of websites, lesson plans, MOOCs, blogs, and tweets, not just traditional books and articles. I have been compiling names over the last three years, and I am now finally getting around to sharing it publicly, in no particular order. While the majority teach social studies education at the university level, others are university history professors, high school teachers, or education consultants. I should also add a disclaimer that the inclusion of a particular individual in this list does not mean I agree with or endorse every opinion they express. My list is by no means exhaustive or conclusive, and I am always open to suggestions. Who do you follow? Click on the names below for academic homepages or personal websites or follow the Twitter handles indicated.

6/13/2015 Are PowerPoint Presentations the New Film Strips? Creating Interactive PowerPoint PresentationsBy Matt Doran  I recently came across my old filmstrip collection, which I believe has now officially passed from audio-visual aid to historic artifact. Most of the filmstrips are accompanied by a cassette tape that beeps as a signal to move to the next slide. Others require human narration. For the record, I am not old enough to have actually taught using filmstrips. I am, however, old enough to have watched them as a student. As I looked through my collection, a question came to mind: has pedagogy changed in thirty years, or are PowerPoint presentations just the new filmstrips? While filmstrips could provide a helpful visual supplement to a lecture, they were largely a passive experience for students. Students might be required to take notes or answer some questions, but the content was largely pre-determined unless the teacher ad-libbed. By the turn of the 21st century, filmstrips, slide projectors, and overhead transparencies were being replaced by PowerPoint presentations. Today, PowerPoint is often viewed a symbol of stand-and-deliver direction instruction (lecturing), which has fallen out of favor for more constructivist pedagogy. As the Grant Wiggins recently noted, history teachers appear to be the most likely to spend a large percentage of time lecturing, at the expense of other student-centered approaches. It is important to remember that PowerPoint is only software with a blank canvas (and some fancy themes). It is neither inherently good nor bad--it all depends on how it is used. A PowerPoint presentation need not be a canned lecture or scripted narration. When used effectively with interactive features, PowerPoint has far greater potential than a prefab film strip. Here are four suggestions for creating interactive PowerPoint presentations. Vocabulary Games Vocabulary instruction is a critical component of students' academic success, and 55 percent of students' academic vocabulary comes from social studies disciplines. In Robert Marzano's Six-Step Process for Building Academic Vocabulary, step 6 requires involving students in games that enable them to play with terms. Games for vocabulary development should include student-to-student interaction. Tech savvy educators have created PowerPoint game templates that can be customized to meet specific course vocabulary. These include games like Password, Pyramid, and Taboo. For more PowerPoint game templates, see the links from FMI Teaching Resources and UNCW EdGames. Teachers can also create their own templates, using hyperlinks within the presentation. (See the directions in the Contingency and Decision-Making section below.) Visual Discovery and Spiral Questions Teachers' Curriculum Institute, publisher of the popular History Alive! materials, uses visual discovery to increase engagement. Students view and interpret a few powerful images on a historical topic. As slides are presented, teachers pose a series of spiral questions on three levels. Students can assume the role of detective as they answer the questions and record notes in a graphic organizer. In Level 1 questions, student detectives gather evidence by identifying the people, places and things. (What do you see in the image?) In Level 2, student detectives begin to interpret the evidence and make inferences about time period, place, or people in the scene. Students should begin to defend their answers with “because” statements. Questions focus on what, when, where, and who. In Level 3, student detectives must use the evidence and their own critical thinking skills to make hypotheses about what is happening and why. Questions at this level emphasize why and how questions and require justifying, synthesizing, predicting, and evaluating. Checking for Understanding - Clickers and Poll Everywhere Student response systems (clickers) provide an easy and quick way for teachers to check for understanding. TurningPoint is an add-in to PowerPoint. Teachers can create new presentations in TurningPoint or use existing PowerPoint presentations and add in new slides. These new slides include multiple choice items in which students can respond to questions with remote response cards. Results are tallied and displayed in a chart in real-time within the PowerPoint presentation. Teachers can save the session to track individual and group progress over time. (Note: Plickers is a free alternative that allows teachers to collect real-time data through a web browser and teacher smart phone or tablet, without the need for student devices.) Poll Everywhere is an app that allows teachers to ask multiple choice or open-ended questions. Teachers create questions using the online app. Once the poll is activated, it can be downloaded as a PowerPoint slide and inserted to another presentation. Students can respond to questions via the web, text message or Twitter. As the students respond, results appear instantly on the slide. Graphs change and move and open ended answers roll in for everyone to see. Poll Everywhere now includes a PollEv Presenter Add-in option for PowerPoint. Teachers can download the add-in to create new polls directly in PowerPoint, and navigate between poll slides. In addition to checking for understanding, Poll Everywhere questions work well as brainstorming warm-up questions, such as a K-W-L activity. Choose Your Own Adventure - Contingency and Decision-Making PowerPoint presentations, like textbooks, often present history as a linear narrative of what happened in the past, without much consideration to contingency and decision-making. In their article, What Does it Mean to Think Historically?, Thomas Andrews and Flannery Burke write, "To argue that history is contingent is to claim that every historical outcome depends upon a number of prior conditions; that each of these prior conditions depends, in turn, upon still other conditions; and so on. . . Contingency demands that students think deeply about past, present, and future. It offers a powerful corrective to teleology, the fallacy that events pursue a straight-arrow course to a pre-determined outcome, since people in the past had no way of anticipating our present world. Contingency also reminds us that individuals shape the course of human events. . ." PowerPoint presentations do not have to flow in sequential order. Instead, slides can be hyperlinked in a such a way that students choose from a set of decision-points and view possible consequences of their choices, allowing students to better understand the underlying and immediate causes of historical events. The Smart Art graphics in PowerPoint provide a variety of options to generate list, process, hierarchy, or relationship graphic organizers. To hyperlink an element of the organizer, click on the element and select Hyperlink from the Insert tab. Next, click on Place in This Document and link to another slide. Above all, simply avoid death by PowerPoint by using the tool to promote interactive and engaging strategies, instead of rote lectures. Echoes and Reflections, a leader in Holocaust education, provided a free, full-day workshop for teachers (English and Social Studies) in our district this week. Our presenter was Alexis Storch, Director of Education at the Center for Holocaust and Humanity Education in Cincinnati, Ohio. She was joined by powerful testimony from John Koenigsberg, a Holocaust survivor. Here are some of the key takeaways for me.

The Humanity of All

Agency and Choice

Propaganda and Prejudice

Telling the Stories

By Matt Doran I had been planning to post this article this week when I learned of the unexpected passing of Grant Wiggins on May 26, 2015. Wiggins was the co-author of Understanding by Design. His work on backward design and inquiry learning has been a powerful influence on my curriculum and professional development work over the years. The article below is written in his memory. For Wiggins' take on UbD and C3, see the blog article, Questions about Questions: NCSS and UbD. Why Use Inquiry Learning in Social Studies?Inquiry involves the pursuit of knowledge and understanding by means of questioning. Inquiry learning is inextricably tied to the disciplines of history and social sciences. The term “history” is derived from the Greek ἱστορία, historia, meaning “inquiry, knowledge acquired by investigation.” History is not a closed narrative recitation of facts, but rather an open investigation that is continually researched, discussed, and debated. Historians seek not only to answer questions about “who, what, and when,” but also “why and how.” They also search for patterns and connections and draw conclusions about historical significance. While historians focus on questions from the past, social scientists use scientific inquiry and research data to draw conclusions about the relationships among individuals in society. Geographers, sociologists, economists, and political scientists use inquiry to help us understand the world and solve the problems we encounter. How Should Teachers Develop Questions for Inquiry Learning? Inquiry learning starts by posing questions or problems. Good inquiry learning, therefore, relies on the use of good questions. The Understanding by Design framework (UbD) provides one approach for helping teachers frame effective questions. UbD emphasizes beginning with the end goals in mind. The UbD process consists of three planning stages: 1) identifying desired results; 2) determining acceptable evidence; and 3) planning learning experiences and instruction. Developing Overarching Essential Questions UbD stage 1 starts with big ideas and enduring understandings. Big ideas are transferrable concepts that anchor the course and focus the curriculum. Big ideas in social studies may focus on abstract concepts such as:

They may also be framed as issues or conflicts:

The five themes of geography can also function as the big ideas:

Enduring understandings are derived from the big ideas and serve as the “moral of the story.” For example, the big ideas of common good and individual liberties could be expressed as: “Democratic governments must balance the common good with individual liberties.” In geography, an enduring understanding about human-environment interaction could read: “Physical environments influence human activities and human activities alter the physical environment.” Flowing from the big Ideas and enduring understandings, overarching essential questions are broad questions that help shape the direction of units of study throughout an entire course. According to UbD, overarching essential questions:

Table 1A. Sample Overarching Essential Questions in Social Studies

Graphic Organizer 1A. Planning Overarching Essential Questions

Developing Compelling Questions The College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework, developed by the National Council for the Social Studies, helps guide the development of unit-specific compelling and supporting questions. C3 uses an Inquiry Arc based on four dimensions of social studies inquiry: 1) Developing questions and planning inquiries; 2) Applying disciplinary concepts and tools; 3) Evaluating sources and using evidence; and 4) Communicating conclusions and taking informed action. Dimension 1 guides the planning of inquiry-based units. The C3 framework states:

In the video below, Kathy Swan, lead writer of the C3 framework, explains two important criteria for compelling questions. Compelling questions must be intellectually meaty and student-friendly. Table 1B. Sample Compelling Questions

Graphic Organizer 1B. Planning Compelling and Supporting Questions Adapted from the Inquiry Design (IDM) Blueprint: http://www.c3teachers.org/idem/

How Should Teachers Implement Essential and Compelling Questions? Essential questions and compelling questions drive student inquiry. Overarching essential questions should be introduced at the beginning of the course, and revisited throughout the year. Compelling questions should be introduced at the beginning of the unit and lesson and guide student assignments and activities throughout the unit. Strategies for Implementing Overarching Essential Questions Overarching essential questions can be placed on large poster-size paper and posted on the classroom walls. These posters serve as reference points for the teacher and students. Allow space on the posters for the class to record thoughts about the essential questions. At the beginning of the course, conduct a class brainstorm on the board and write some of the key ideas on the posters. Repeat the activity quarterly or with each unit and add the new information using a different color marker each time. This will allow students to see their growth in understanding throughout the course. Students can also keep an essential questions journal to record their reflections on these questions at various points throughout the course. Journal entries also allow for creative responses. Students may draw a cartoon, write a poem or song, or create a visual metaphor to demonstrate their understanding of the questions. Discussion strategies provide opportunities for collaborative reflection on the essential questions. As the questions are revisited, students should be asked to connect the essential questions with the specific content of each unit, with compelling questions serving as further discussion points. While essential questions do not have a single correct answer, they can shape essays in pre- and post-assessments to measure students’ growth in historical thinking and writing. Teachers can assess students’ responses using an evidence-based essay rubric that measures how well students supported their claims with evidence and reasoning. Strategies for Implementing Compelling Questions Compelling questions are unit-specific and should be introduced at the beginning of each unit or lesson. The C3 framework recommends that students take an active role in the development of compelling questions. Teachers may want to develop one or two compelling questions and have students come up with a third question for a particular unit. Keep in mind that compelling questions are only the beginning of the inquiry. Supporting questions should also be crafted to guide students’ inquiry. The strategies contained in the document provide tools for students to research, discuss, and debate these questions, and guidance on performance-based assessment development. Many compelling and supporting questions work well with a detective model approach to history. Like detectives, historians define a specific problem to solve, ask meaningful questions, evaluate the evidence, and draw tentative conclusions. The evidence comes in the form of primary and secondary sources, but is always incomplete. Detectives and historians must try to separate fact from opinion and remain open to a variety of ways the evidence may be interpreted. To begin the detective model, ask students ask students to give examples of detective or investigative television shows or movies they have seen. Ask students to brainstorm a list of skills that a good detective or investigator needs to have. Explain that throughout this course, students will learn that history is not a giant list of facts and figures to memorize. Rather it is an investigation into the past. Ask: Which of these skills are necessary to study history effectively? View a short video clip of a detective show and discuss how the detectives gather and use evidence. Classic examples from the television detective show Dragnet are available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/user/50sDragnet. Graphic Organizer 1C. Investigating History

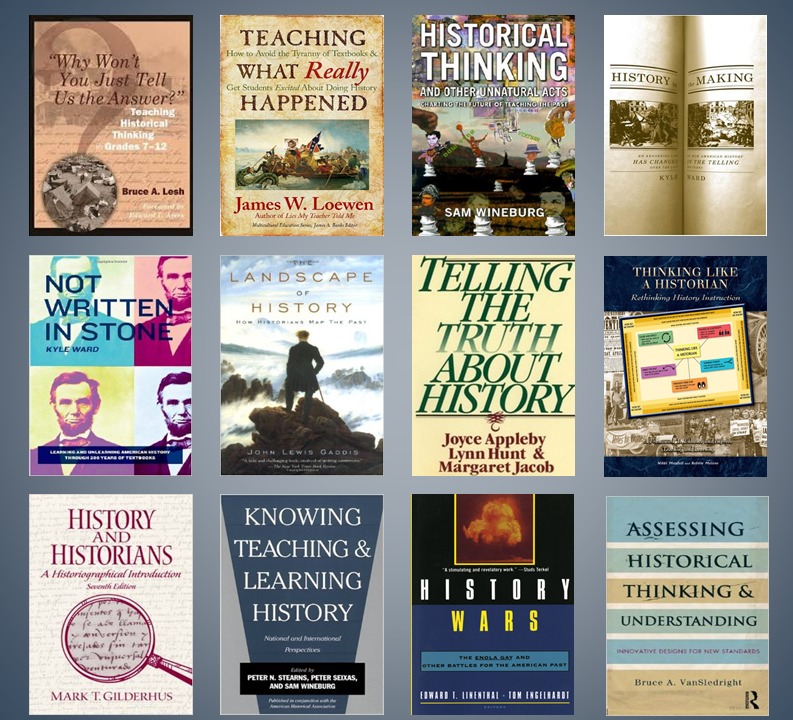

What Resources Are Available for Inquiry Learning? Publications

Wiggins, Grant P., and Jay McTighe. Understanding by Design. Expanded 2nd ed. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2005 McTighe, Jay, and Grant P. Wiggins. Understanding by Design: Professional Development Workbook. Alexandria, Va.: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2004. National Council for the Social Studies. College, Career, and Civic Life Framework for Social Studies State Standards: Guidance for Enhancing the Rigor of K-12 Civics, Economics, Geography, and History. Silver Spring, MD: NCSS, 2013. http://www.socialstudies.org/system/files/c3/C3-Framework-for-Social-Studies.pdf Swan, Kathy and John Lee, ed. Teaching the College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework: A Guide to Inquiry-Based Instruction in Social Studies. Silver Spring, MD, NCSS, 2014 Lesh, Bruce A. "Why Won't You Just Tell Us the Answer?": Teaching Historical Thinking in Grades 7-12. Portland, Me.: Stenhouse Publishers, 2011. Wineburg, Sam, Daisy Martin and Chauncey Monte-Sano. Reading Like a Historian: Teaching Literacy in Middle and High School History Classrooms. Columbia: Teachers College Press, 2012. Websites Stanford History Education Group. Reading Like a Historian. https://sheg.stanford.edu/rlh University of Maryland Baltimore County. History Labs: A Guided Approach to Historical Inquiry in the K-12 Classroom. http://www.umbc.edu/che/historylabs/ National Council for the Social Studies. C3 Teachers: College, Career & Civic Life. http://www.c3teachers.org/ For the past ten years, I have been developing district micro-curriculum--course-specific unit plans and model lessons. This summer I am tackling a project that will yield a broader view of secondary social studies. The Social Studies Instructional Framework will be a macro-curriculum outlining the elements of successful social studies units, applicable to all courses and grade levels, 6-12.

This macro-curriculum will extrapolate the underpinning pedagogy from the course-specific lessons and synthesize the parallel work I have been generating for professional development workshops. Through a combination of narrative, samples, and blank organizers, the Social Studies Instructional Framework will help guide teachers in the preparation of units and lessons (or the adaptation of existing ones). The end product will essentially be a condensed version of a social studies methods textbook. As I work through the Social Studies Instructional Framework this summer, I will post drafts on this blog to invite feedback from teachers and scholars. Today, I have included the draft outline of the chapters and sections. Your comments are welcome. What would you include, or not include? Elements of Successful Social Studies Units 1. Inquiry Questions

2. Performance-Based Assessment

3. Vocabulary Development

4. Graphically-Organized Notes

5. Social Studies Skills

6. Reading Like a Historian

7. Evidence-Based Writing

8. Discussion and Debate

9. Role-Play and Simulation

10. Relevance, Real World Connections and Civic Engagement

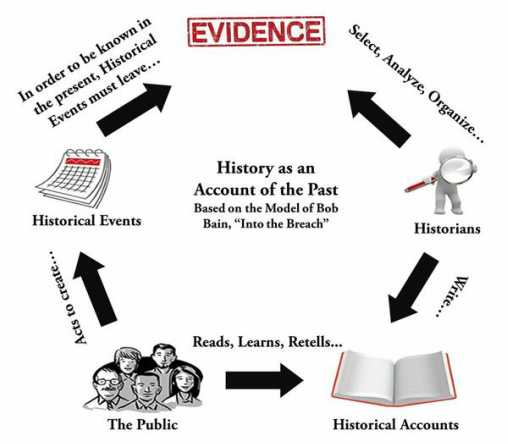

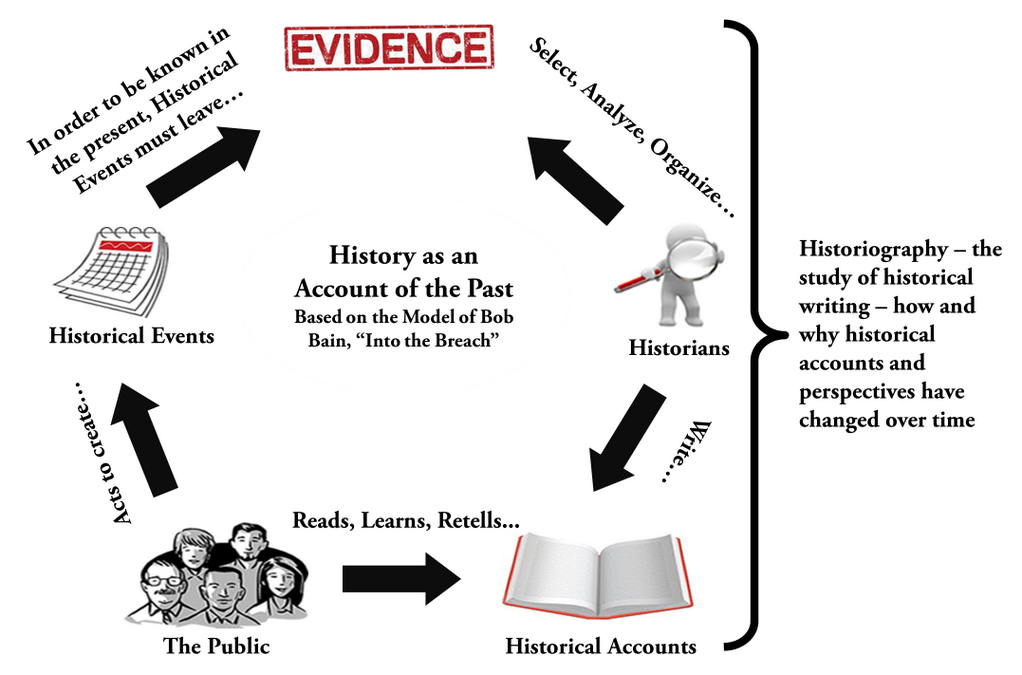

By Matt Doran Skills: What do we want students (citizens) to able to do? Critically analyze perspectives in secondary sources, situating these sources in their social and political context to determine factors that shape historians’ perspectives on the past. "Each age tries to form its own conception of the past. Each age writes the history of the past anew with reference to the conditions uppermost in its own time." - Frederick Jackson Turner Thomas Jefferson: apostle of agrarian democracy? Champion of the rights of the common people? Enlightenment skeptic? Liberal capitalist? Southern aristocrat? Racist? Suppressor of civil liberties? These were among the historiographical questions that shaped an undergraduate course I took called Jeffersonian and Jacksonian Democracy. I had been introduced to historiography a year earlier, in “Introduction to Historical Thought,” a gateway course to the history major. Historiography is the study of historical writing—examining the history of historical perspectives with attention to the social and political context of each generation (or school) of historians. Historiography considers why and how history changes over time. I learned about historiography in other courses as well, but in Jeffersonian and Jacksonian Democracy we did historiography. We looked at Jefferson and Jackson through a critical analysis of secondary sources, using a three-pronged heuristic adapted from Robert Berkhofer’s “Demystifying Historical Authority” 1. What is the surface meaning? 2. What could have been said, but wasn’t? 3. What intellectual underpinnings shape the historian’s perspective? But, that was college…and an upper-level undergraduate class…for history majors. Can secondary social studies teachers employ a similar approach? In Teaching What Really Happened, James Loewen’s answer is a definitive “yes.” In fact, Loewen has introduced historiography to students as young as fourth grade, noting that “if they can learn supercalifragilisticexpialidocious, they can handle historiography.” As a high school teacher, I incorporated some elements of historiography into instruction. We looked at various textbook titles and covers from American history textbooks of different eras. What does the title Two Centuries of Progress (1978) imply? Is there a difference between Rise of the American Nation (1977) and Out of Many: A History of the American People (2001)? What change in front material do you notice in textbooks published shortly after 2001? (inclusion of patriotic inserts such as the Pledge of Allegiance) How did changing social and political concerns influence these titles? We also looked at various interpretations of the American Revolution, the Early Republic and the Civil War and Reconstruction—mostly with me explaining those views. What I did not establish, however, was a comprehensive approach that required students to do historiography consistently throughout the year. Since leaving the classroom for full-time curriculum and professional development work, I have gathered a set of resources and developed strategies and tools fordoing historiography in the secondary classroom. A Conceptual Framework of History Before students dig into historiography, they need to be grounded in an understanding of the nature of history. Bob Bain’s conceptual model from “Into the Breach” is one method for introducing the discipline of history. The adaptation below shows the relationship between past events, evidence, historians, and historical accounts. Once students are comfortable with this model of history, teachers can add the historiography layer. Getting Started with Historiography As with other challenging social studies concepts, the best starting point is to access students’ prior knowledge and build on what they already know. Rather than starting with Jefferson and Jackson, look first at popular examples that relate to students lives more directly. For example, how did sportswriters in Cleveland interpret LeBron James in 2003? in 2011? in 2014? Was he viewed as a hero or villain? How did the changing context (the changing teams) shape their interpretation of James? (See the video link here for Kyle Ward’s Brett Favre analogy). Just as our perspectives on the present are shaped by our worldview (and personal loyalties), historians’ view the past through the lens of contemporary concerns and ideologies. As a transition from popular examples to historical perspectives, have students work in groups to summarize and evaluate some of the following quotes that illustrate the concept of historiography:

Unpacking Secondary Sources Historians do not limit their investigation of evidence to primary sources. They also read what other historians have written and how those historians used their evidence. Students should do this as well. As Joe Sangillo, Social Studies Curriculum Specialist with Montgomery County Schools, tweets: If you need a rationale for incorporating historiography and secondary source analysis, note the following Common Core Literacy in History/Social Studies Standards:

James Loewen suggests ten questions that can be applied to a variety of secondary sources (historic site, documentary film, textbook, etc.)

See James Loewen, Teaching What Really Happened: How to Avoid the Tyranny of Textbooks and Get Students Excited About Doing History Again, starting with relevant and accessible examples will help students learn the work of historiography before ultimately moving on to more complex historical monographs. Consider some of the strategies below. Nostalgia Sitcoms View episodes of nostalgia sitcoms such as Happy Days, Wonder Years, or The Goldbergs. These shows are set in an earlier historical period. Happy Days, (1974-1984), presents an interpretation of life in the 1950s. What interpretation of the 1950s is portrayed? (hint: consider the show’s title). What aspects of the 1950s are left out? (hint: see Michael Harrington’s The Other America). What social and political conditions in the late 1970s might have caused the producers and the American public to long for a happier era? The Wonder Years (1988-1993) portrays life in the late 1960s and early 1970s—tackling issues like the Vietnam War, counterculture movement, and the cultural divide between generations. Who might have been the target audience for this show? What cultural and economic trends in the 1990s may have influenced the writers’ decision to point out some of the turbulent aspects of the 1960s and 1970s? Historic Markers Choose an historic marker in the neighborhood and analyze the narrative presented on the marker. Loewen argues that every historic marker is “a tale of two eras: what it’s about and when it went up.” In other words, the historical narrative presented reflects the social and political context in which the marker was created, and the beliefs and values of the sponsoring organization. Loewen documents examples of these markers in Lies Across America: What Our Historic Sites Get Wrong. Loewen’s suggested questions above are helpful for analyzing marker texts. Textbooks Instead of abandoning textbooks altogether, we should consider new ways of using them. Textbooks can be artifacts for analysis. Rather than looking at the text as an authority from which to glean truth, an historiographical approach requires students to ask questions about what is and is not included in a text, how various events and individuals are portrayed, what visuals are chosen to supplement the narrative, etc. Bob Bain offers a step-by-step approach for questioning textbook authority:

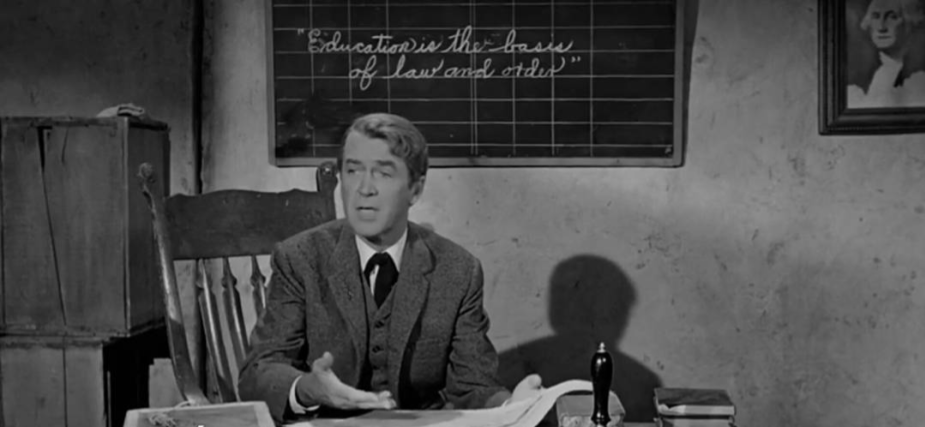

Kyle Ward’s book, History in the Making presents textbook excerpts from 200 years of American history, looking at how interpretations of familiar historical events have changed over time. Not Written in Stone offers an abridged and annotated version History in the Making designed for classroom use. In each section, Ward provides an overview and questions for discussions for each set of excerpts. Students can use the graphic organizer linked here to analyze these excerpts and other secondary accounts. Assessments and Additional Resources The Stanford History Education Group’s Beyond the Bubble: History Assessments of Thinking work well for assessing students’ skills in historiography. The John Brown’s Legacy assessment asks students to examine a poster for a play written in 1936 that celebrates the abolitionist John Brown. Students must situate the playbill in time, understanding how the anti-lynching campaign of the 1930s and the rise of fascism in Germany may have motivated the authors to write a play as a commentary on racism. A similar assessment on Creating Columbus Day (during the Gilded Age) asks why President Harrison declared Columbus Day a national holiday in 1892. Students should explain that Harrison’s decision might have been a calculated move to court Catholic voters in the upcoming election. Russel Tarr’s Active History website offers a collection of resources on historiography designed for use in IB History, but adaptable for other secondary history classrooms. The resources include lectures on various theories of historical causation, student activities, and a historiographical terms handout. See the video clips and book titles below for additional resources on historiography. Teaching students to do historiography in the secondary classroom is not an easy task. However, with the right resources, tools, and scaffolds it is an achievable task. As Loewen notes, “historiography is one of the great gifts that history teachers can bestow upon their students.” I welcome your thoughts on how we can work to bestow this gift to students. By Matt Doran Skills: What do we want students (citizens) to able to do? Analyze perspectives in primary and secondary sources, and evaluate the credibility of information in historical and contemporary sources. Today I am sharing three short videos that can help teachers sharpen students' skills in source analysis: 1. Primary vs. Secondary Sources 2. The Guardian Commercial: Points of View 3. How to Choose Your News In the classroom, you may want to pause the clip after each point of view is shown. Have students make inferences about what is happening based on the point of view they have just seen. By Matt Doran Dispositions: 3) What do we want students (citizens) to value? Appreciate the importance of literacy and civic education in the success of the American republic. It’s back to school week for many teachers and students—a good time to remind ourselves of the purpose of public education. In recent years, many schools have adopted STEM-focused programs and career pathways mission statements. To be sure, these are good and necessary aspects of a well-rounded education. We should not, however, allow these emphases to distract us from the fundamental civic mission of education in the United States – a mission deeply rooted in the history of the American republic. Thomas Jefferson believed that education and civic virtue must go hand in hand-in-hand in a successful republic. By teaching citizens of their right to self-government, education serves as the guardian of democracy. Noting the historical propensity for governments to be “perverted into tyranny,” Jefferson argued that knowledge of this history was the best safeguard against it. Moreover, liberal education was necessary for leaders who would “guard the sacred deposit of the rights and liberties of their fellow citizens….” In his “Report of the Commissioners Appointed to Fix the Site of the University of Virginia, 1818” Jefferson further outlined the civic purposes of education—improving morals through reading, understanding duties and rights, and exercising of sound judgment. To accomplish these ends, citizen students should learn reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, history, the principles of government, and perhaps most importantly, “a sound spirit of legislation, which…shall leave us free to do whatever does not violate the equal rights of another…” Fast forward to the second half of the 20th century. The U.S. and Soviet Union were engaged in a Cold War “space race” that stimulated an increased emphasis (and funding) on science and math education in the United States. At the height of the Cold War in 1962, producer John Ford reminded his viewers of the civic mission of education in his Western film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. The film’s main character, Ransom Stoddard (played by Jimmy Stewart), established a school in the “uncivilized” town of Shinbone to teach literacy and Enlightenment principles of American self-government. The classroom chalkboard revealed Stoddard’s Jeffersonian vision of education and citizenship: “Education is the basis of law and order”—emphasizing both the instrumental purpose of education and the order of operations. Education must come first, for it teaches citizens that they are rational people, entitled to have liberty and self-government, capable of maintaining it, and willing to do so for the good of the community. Education emerged in response to the need for a virtuous citizenry that could create a civilized society by establishing law and order and removing the obstacles to it. Stoddard’s pupils learned that they have a republic, which one immigrant woman defined as “the people are the boss… If the people in Washington don’t do what we want, we vote them out.” Governing power rests with the electorate who exercise their power through the vote, Stoddard explained. To help his pupils apply their understanding of self-government and the power of the vote, Stoddard used a newspaper article that outlined the potential impact of the cattle ranchers’ efforts to fight statehood. The consequences would be the loss of local control and small shops, and a way of life for these small communities. This effort could only be stopped by the power of the electorate. In doing so, they would also stop Liberty Valance who worked as the ranchers’ lead ruffian. While Valance terrorized the town, Shinbone’s duty constituted law and order, Marshal Appleyard, was paralyzed by fear. He showed no interest in education and, consequently, did nothing to guard the safety of the community. He had no intrinsic understanding of self-government—its historical and philosophical basis— and why this is worth preserving. In short, he was uneducated. Once armed with education, Shinbone’s citizens could select delegates to the legislature, resist the efforts of the big ranchers to block statehood, and render Liberty Valance obsolete. In this present world of 21st century learning, we should not lose sight of the historical centrality of civic education in America. According to one story, Benjamin Franklin, upon leaving the Constitutional Convention, was asked what sort of government the delegates had created. His answer: “A republic, if you can keep it.” Indeed, successful republics—both then and now—demand not only the consent of the people, but also the education and active engagement of its citizens. |

Blog Categories

All

Blog Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

7/4/2015

3 Comments