Reflections and Collections for the 21st Century Social Studies Classroom

|

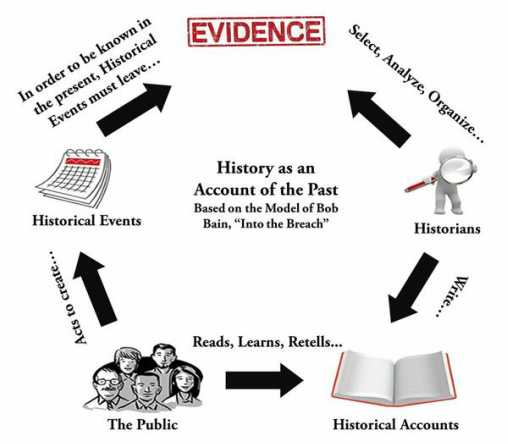

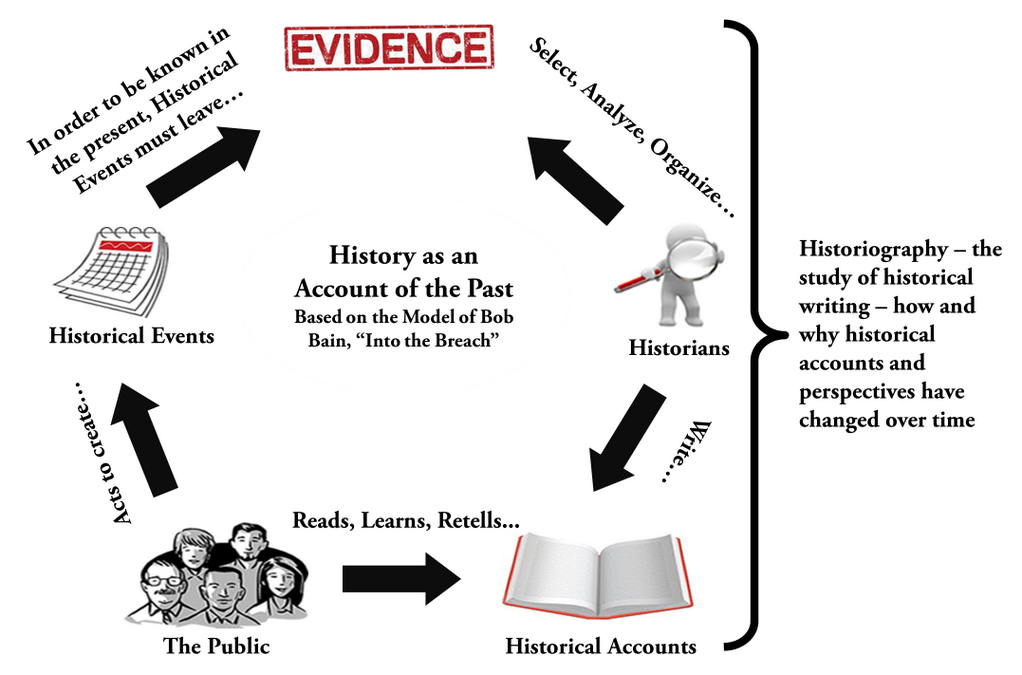

By Matt Doran Skills: What do we want students (citizens) to able to do? Critically analyze perspectives in secondary sources, situating these sources in their social and political context to determine factors that shape historians’ perspectives on the past. "Each age tries to form its own conception of the past. Each age writes the history of the past anew with reference to the conditions uppermost in its own time." - Frederick Jackson Turner Thomas Jefferson: apostle of agrarian democracy? Champion of the rights of the common people? Enlightenment skeptic? Liberal capitalist? Southern aristocrat? Racist? Suppressor of civil liberties? These were among the historiographical questions that shaped an undergraduate course I took called Jeffersonian and Jacksonian Democracy. I had been introduced to historiography a year earlier, in “Introduction to Historical Thought,” a gateway course to the history major. Historiography is the study of historical writing—examining the history of historical perspectives with attention to the social and political context of each generation (or school) of historians. Historiography considers why and how history changes over time. I learned about historiography in other courses as well, but in Jeffersonian and Jacksonian Democracy we did historiography. We looked at Jefferson and Jackson through a critical analysis of secondary sources, using a three-pronged heuristic adapted from Robert Berkhofer’s “Demystifying Historical Authority” 1. What is the surface meaning? 2. What could have been said, but wasn’t? 3. What intellectual underpinnings shape the historian’s perspective? But, that was college…and an upper-level undergraduate class…for history majors. Can secondary social studies teachers employ a similar approach? In Teaching What Really Happened, James Loewen’s answer is a definitive “yes.” In fact, Loewen has introduced historiography to students as young as fourth grade, noting that “if they can learn supercalifragilisticexpialidocious, they can handle historiography.” As a high school teacher, I incorporated some elements of historiography into instruction. We looked at various textbook titles and covers from American history textbooks of different eras. What does the title Two Centuries of Progress (1978) imply? Is there a difference between Rise of the American Nation (1977) and Out of Many: A History of the American People (2001)? What change in front material do you notice in textbooks published shortly after 2001? (inclusion of patriotic inserts such as the Pledge of Allegiance) How did changing social and political concerns influence these titles? We also looked at various interpretations of the American Revolution, the Early Republic and the Civil War and Reconstruction—mostly with me explaining those views. What I did not establish, however, was a comprehensive approach that required students to do historiography consistently throughout the year. Since leaving the classroom for full-time curriculum and professional development work, I have gathered a set of resources and developed strategies and tools fordoing historiography in the secondary classroom. A Conceptual Framework of History Before students dig into historiography, they need to be grounded in an understanding of the nature of history. Bob Bain’s conceptual model from “Into the Breach” is one method for introducing the discipline of history. The adaptation below shows the relationship between past events, evidence, historians, and historical accounts. Once students are comfortable with this model of history, teachers can add the historiography layer. Getting Started with Historiography As with other challenging social studies concepts, the best starting point is to access students’ prior knowledge and build on what they already know. Rather than starting with Jefferson and Jackson, look first at popular examples that relate to students lives more directly. For example, how did sportswriters in Cleveland interpret LeBron James in 2003? in 2011? in 2014? Was he viewed as a hero or villain? How did the changing context (the changing teams) shape their interpretation of James? (See the video link here for Kyle Ward’s Brett Favre analogy). Just as our perspectives on the present are shaped by our worldview (and personal loyalties), historians’ view the past through the lens of contemporary concerns and ideologies. As a transition from popular examples to historical perspectives, have students work in groups to summarize and evaluate some of the following quotes that illustrate the concept of historiography:

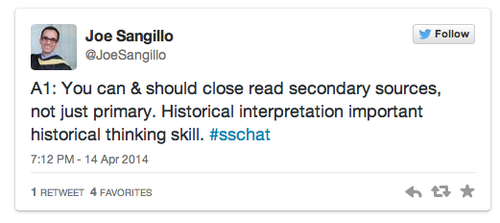

Unpacking Secondary Sources Historians do not limit their investigation of evidence to primary sources. They also read what other historians have written and how those historians used their evidence. Students should do this as well. As Joe Sangillo, Social Studies Curriculum Specialist with Montgomery County Schools, tweets: If you need a rationale for incorporating historiography and secondary source analysis, note the following Common Core Literacy in History/Social Studies Standards:

James Loewen suggests ten questions that can be applied to a variety of secondary sources (historic site, documentary film, textbook, etc.)

See James Loewen, Teaching What Really Happened: How to Avoid the Tyranny of Textbooks and Get Students Excited About Doing History Again, starting with relevant and accessible examples will help students learn the work of historiography before ultimately moving on to more complex historical monographs. Consider some of the strategies below. Nostalgia Sitcoms View episodes of nostalgia sitcoms such as Happy Days, Wonder Years, or The Goldbergs. These shows are set in an earlier historical period. Happy Days, (1974-1984), presents an interpretation of life in the 1950s. What interpretation of the 1950s is portrayed? (hint: consider the show’s title). What aspects of the 1950s are left out? (hint: see Michael Harrington’s The Other America). What social and political conditions in the late 1970s might have caused the producers and the American public to long for a happier era? The Wonder Years (1988-1993) portrays life in the late 1960s and early 1970s—tackling issues like the Vietnam War, counterculture movement, and the cultural divide between generations. Who might have been the target audience for this show? What cultural and economic trends in the 1990s may have influenced the writers’ decision to point out some of the turbulent aspects of the 1960s and 1970s? Historic Markers Choose an historic marker in the neighborhood and analyze the narrative presented on the marker. Loewen argues that every historic marker is “a tale of two eras: what it’s about and when it went up.” In other words, the historical narrative presented reflects the social and political context in which the marker was created, and the beliefs and values of the sponsoring organization. Loewen documents examples of these markers in Lies Across America: What Our Historic Sites Get Wrong. Loewen’s suggested questions above are helpful for analyzing marker texts. Textbooks Instead of abandoning textbooks altogether, we should consider new ways of using them. Textbooks can be artifacts for analysis. Rather than looking at the text as an authority from which to glean truth, an historiographical approach requires students to ask questions about what is and is not included in a text, how various events and individuals are portrayed, what visuals are chosen to supplement the narrative, etc. Bob Bain offers a step-by-step approach for questioning textbook authority:

Kyle Ward’s book, History in the Making presents textbook excerpts from 200 years of American history, looking at how interpretations of familiar historical events have changed over time. Not Written in Stone offers an abridged and annotated version History in the Making designed for classroom use. In each section, Ward provides an overview and questions for discussions for each set of excerpts. Students can use the graphic organizer linked here to analyze these excerpts and other secondary accounts. Assessments and Additional Resources The Stanford History Education Group’s Beyond the Bubble: History Assessments of Thinking work well for assessing students’ skills in historiography. The John Brown’s Legacy assessment asks students to examine a poster for a play written in 1936 that celebrates the abolitionist John Brown. Students must situate the playbill in time, understanding how the anti-lynching campaign of the 1930s and the rise of fascism in Germany may have motivated the authors to write a play as a commentary on racism. A similar assessment on Creating Columbus Day (during the Gilded Age) asks why President Harrison declared Columbus Day a national holiday in 1892. Students should explain that Harrison’s decision might have been a calculated move to court Catholic voters in the upcoming election. Russel Tarr’s Active History website offers a collection of resources on historiography designed for use in IB History, but adaptable for other secondary history classrooms. The resources include lectures on various theories of historical causation, student activities, and a historiographical terms handout. See the video clips and book titles below for additional resources on historiography. Teaching students to do historiography in the secondary classroom is not an easy task. However, with the right resources, tools, and scaffolds it is an achievable task. As Loewen notes, “historiography is one of the great gifts that history teachers can bestow upon their students.” I welcome your thoughts on how we can work to bestow this gift to students. |

Blog Categories

All

Blog Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

10/18/2014

4 Comments