Reflections and Collections for the 21st Century Social Studies Classroom

|

By Matt Doran

What can you do to continue the learning at home during the extended school closure? If you are a social studies teacher or interested parent, you really don’t need the latest temporarily-free app. Instead, pose these three questions:

Watch/read the news and write a daily journal reflection on these questions. When the crisis is over, you will have created a new primary source about this event. Then, go back through history and make connections and comparisons across time and place. Here is a historical look at question 3 since 1958 from the Pew Research Center: Public Trust in Government: 1958-2019. Your students will learn way more from this exercise than filling out digital worksheets. By Matt Doran In times of crisis, history helps us keep things in perspective. Seventy-five years ago, men and women of the Greatest Generation were fighting on the battlefields and working in the factories to defend democracy. Worldwide, more than 15,000,000 soldiers and 45,000,000 civilians died. My maternal grandfather, Pfc. Fred Rish, wrote these words on March 15, 1945 from the Philippines: Dear Mom: Read the full collection of letters at WarMemory.com. by Matt Doran

If we want to find enduring relevance in education, we must draw from the deep cultural foundations of history and philosophy, not economic and business principles. Education is a social institution with a civic mission. It's not enough to define what we want students to know and be able to do. We must also wrestle with the question: What do we want to students to value? College and Career Readiness is a necessary, but not a sufficient mission for schools. A more comprehensive vision needs to include College, Career, and Civic Life Readiness. The Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools defines civic dispositions as a concern for others' rights and welfare, fairness, reasonable levels of trust, and a sense of public duty. Civic dispositions are crucial to democratic character formation, and the sustainability and improvement of constitutional democracy. If standards must drive our work, then we need a set of civic anchor standards to match those that define critical knowledge and skills. One good option is to pair some of the indicators from the C3 Framework with the Social Justice Standards from Teaching Tolerance. From the C3 Framework: Dimension 2. Civics: Participation and Deliberation: Applying Civic Virtues and Democratic Principles

Dimension 4. Taking Informed Action

From the Teaching Tolerance Social Justice Standards: Identity Anchor Standards

Diversity Anchor Standards

Justice Anchor Standards

Action Anchor Standards

7/11/2019 Wineburg on Media LiteracyFrom Why Learn History (When It's Already on Your Phone) by Sam Wineburg. "Wedging a media literacy course into an already crammed curriculum is like slapping a new coat of paint on a house that's teetering on its foundation: it lends to better street appeal but it does little to address the underlying problem. Making headway will entail more than a four-week media or news literacy course. It will require a fundamental reorientation to the curriculum. . . . What once fell on the shoulders of editors, publishers, librarians, and subject matter experts now falls on the shoulders of each and every one of us. The big problem with this new reality is that the ill-informed hold just as much power at the polling station as the well-informed. Reliable information is to civic intelligence what clean air and water are to public health. . . . Jefferson's solution is no less apt today than it was in his era. 'If we think [the people] are not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not take it from them, but to inform their discretion by education.'" - Sam Wineburg by Matt Doran

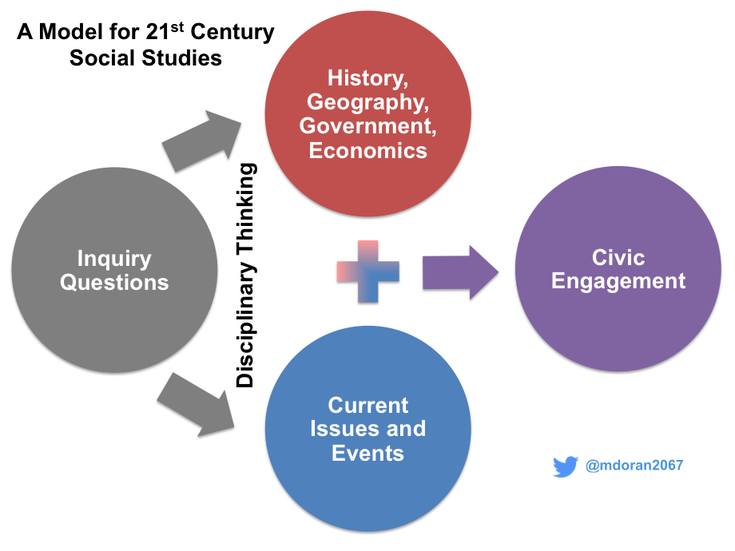

This month we began year three of our middle school professional development program, with an emphasis on pedagogical content knowledge. We are focusing our discussions on creating and implementing a vision for social studies in alignment with the C3 Framework. Since social studies is not a state-tested subject in Ohio middle schools, there is often a perception that it is the least important of the core subjects. Balderdash. The opposite is true: Social studies is too important to force into the constraints of state testing. Free from the yoke of testing, middle school social studies teachers have the freedom and flexibility to execute a vision of social studies education that aligns with both the original intent of social studies and its vital purpose in 21st century democracies. The skills, reasoning capacities, and civic dispositions social studies cultivates cannot be effectively captured through a standardized test. The centrality of social studies among the school subjects lies not in its place within the cesspool of corporate testing and sham accountability systems, but in its instrumental purpose in modern democracies. As conceived by the Report of the Social Studies Committee in 1916, social studies is a discipline designed to actualize a Deweyan vision of pragmatism in education. Drawing from a wide-range of disciplines in the humanities and social sciences, social studies aims to tap into students’ interests and use inquiry-learning to solve real-world problems. Its purpose is explicitly instrumental: to improve society. Having emerged in the Progressive Era, the creation of the social studies in school curricula was part of a broader response to the ills and excesses of Gilded Age industrial capitalism. The Progressive Era ushered in democratic reforms in states (referendum, initiative, recall) and the U.S. Constitution (17th and 19th amendments). Laws were passed to safeguard food production and the environment, limit the power of corporate trusts and monopolies, and establish compulsory public education. In the decades since the Progressive Era, historians and social scientists of the various disciplines that make-up social studies have defined thinking skills central to the disciplines. Such skills include conducting original research, contextualizing historical sources, creating and analyzing data sets, evaluating sources, supporting arguments with evidence, and unpacking cause-and-effect relationships. Many scholars today argue that we are living in a Second Gilded Age, defined by social and economic inequality and political corruption. Even if one doesn’t agree with this characterization of our present times, it is difficult to imagine a case being made against the critical importance of social studies in the 21st century. Do we need increased civic engagement, better civil discourse, more cultural awareness, heightened concern for social justice, greater discernment in evaluating the credibility of information, creative cross-disciplinary solutions to real-world problems, and sharper ethical thinking skills? If so, then we need more social studies, not less. As Natalie Wexler has written in a recent Forbes article, “We know that only a minority of students will end up working in STEM fields. But virtually all will be expected to exercise their rights and responsibilities as citizens of a democracy.” With great freedom comes great responsibility. As social studies teachers, we bear the responsibilities of communicating the importance of our vision to the broader community, and designing and aligning our curriculum to meet this instrumental purpose. We cannot decry state testing on the one hand, while continuing to pack our non-tested courses with a superfluity of Googleable names, dates, and facts on the other. In Why Learn History, When It’s Already on Your Phone, Sam Wineburg describes the ongoing work of the Stanford History Education Group to “change history class from a forced march through an all-knowing textbook to a journey where students, to invoke the late Ted Sizer, ‘learn to use their minds well.’ ” In practice, this requires more student-centered inquiry, research, problem solving, disciplinary thinking, discussion, presentations, and taking informed civic action. by Matt Doran

This year’s election was a keen reminder to all of us in the civic education community of the importance of teaching students how to evaluate online information. Fake news--in the form of click bait, political propaganda, falsified images, and spurious memes--permeates social media feeds today. Craig Silverman of Buzzfeed highlights the problem in the video linked here. How do we teach students (and citizens) to evaluate online information in order to make informed decisions? The Stanford History Education Group (SHEG) and the News Literacy Project (NLP) are both taking up the worthy task helping students evaluate online information. SHEG has recently developed and administered assessment tasks for civic online reasoning--the ways in which students search for, assess, and evaluate online information. Civic online reasoning consists of three core competencies: 1) Who is behind the information? 2) What is the evidence? and 3) What do other sources say? In increasing order of complexity, here are three performance tasks SHEG developed to assess students' use of online information.

The News Literacy Project has developed a suite of teaching tools and elearning modules for evaluating online information:

We have much work to do in the field of civic education in order to help our students become informed participatory citizens. As the methods of receiving and processing information change in the 21st century, our teaching approaches must keep up. SHEG’s civic online reasoning and NLP’s news literacy tools can help us accomplish this task. by Matt Doran  Many observers of contemporary American politics believe we have reached the pinnacle of demagoguery and political posturing. True enough, negative campaigning, vitriolic personal attacks, divisive rhetoric, and other forms of incivility, are commonplace today. This conclusion, however, is drawn from a presentist view of the world, rather than from clear historical thinking. Historically speaking, incivility has been a rule rather than an exception in American politics. It is, however, a rule that surely needs to be (and indeed can be) broken. The use of demagoguery—an appeal to people that plays on their emotions and prejudices rather than on their rational side—is as old as politics itself, dating back to Ancient Greece. The American founders understood this propensity. Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist 71, notes, “The republican principle… does not require an unqualified complaisance…to every transient impulse that people may receive from the arts of men who flatter their prejudices to betray their interests.” In Federalist 55, James Madison argues, “In all very numerous assemblies … passion never fails to wrest the sceptre from reason.” In one of first contested presidential elections in 1800, the campaigns of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams engaged in an acerbic war of words. Among other things, Jefferson supporters called Adams a "hideous hermaphroditical character." In turn, Adams supporters branded Jefferson “the son of a half-breed Indian squaw, sired by a Virginia mulatto father,” “an atheist," and “a coward.” The legendary Lincoln-Douglas Senate debates of 1858 were equally vicious, sardonic, and crude. Douglas repeatedly referred to Lincoln’s "Black Republican" party and made frequent use of the N-word. No doubt, hundreds of similar examples could be culled from the archives of twentieth century elections as well. To point out this history is not to suggest that we should lose hope in a better America. To the contrary, knowing this history is the first step in overcoming it. What we need is not a return to some mythical golden age of politics and statesmanship, but to move beyond the vices of our fathers and our own base instincts. In short, we need a new era of reasoned civil discourse grounded in logic, humility, and empathy. The key to the future, therefore, lies in humanities education. As Sam Wineburg argues, “My claim in a nutshell is that history holds the potential, only partly realized, of humanizing us in ways offered by few other areas in the school curriculum. … Each generation must ask itself anew why studying the past is important, and remind itself why history can bring us together rather than—as we have seen most recently—tear us apart.” First, history teaches us how to think. History and civics education must go beyond a curriculum mired in trivia and facts. The answers to the questions we pose should not be Googleable. We must engage students in the compelling, philosophical, and persistent questions that shape humanity. As students pursue answers to these questions, they learn to gather evidence, make inferences, contextualize sources, distinguish facts from value judgments, and identify fallacious reasoning. Second, when we encounter a multiplicity of voices and human experiences, we are humbled by the vast sea of events, information and ideas, and how little we know. Doing history teaches us to avoid hard-and-fast conclusions, but rather to hold suppositions as tentative. The past is gone; only remnants remain. Sometimes new remnants come to light or new ways of looking at old remnants are encouraged, forcing us to rethink our interpretations. Third, history teaches empathy. Empathy is walking in another person’s shoes, the experience of understanding another person's condition from their perspective. As Jason Endocott and Sarah Brooks write, “historical empathy is the process of students’ cognitive and affective engagement with historical figures to better understand and contextualize their lived experiences, decisions, or actions.” The methods we use to teach history are important to cultivating these dispositions. The Structured Academic Controversy (SAC) is a good starting point. This strategy blends the best of evidence-based argumentation with civil discourse. As described on the Teaching American History Clearinghouse website:

The Center for Civic Education’s We the People program is another model program for engaging students in civil discourse. Teams of students prepare oral arguments for a simulated Congressional hearing before a panel of judges, and respond to follow-up questions from the judges. Unlike many recent presidential debates, questions in We the People are deep, philosophical, and provocative. Here is a sample from this year’s national competition:

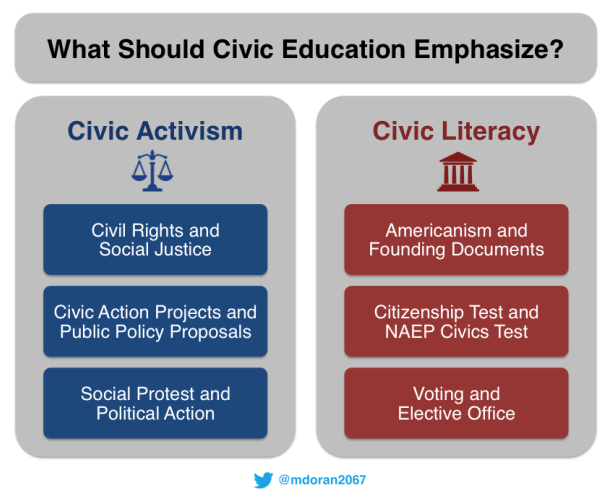

For fostering both historical thinking and historical empathy, Reacting to the Past, an increasingly popular approach used in university history courses, has created a standard for K-12 to follow. The methodology consists of course-long simulations, set in historical context. Students are drawn into the past with assigned roles informed by classic texts. Class discussions and presentations are run by students, with guidance and evaluation from the instructor. Indeed, American politics is, and has been historically, an ugly sphere. But the future can be brighter when the light of history, through the lens of logic, humility and empathy, shines upon it. 12/22/2015 What Should Civic Education Emphasize?by Matt Doran Recent developments have raised questions about what kind of civic education we should have in the United States. Critics of the College Board's new AP US History Framework claimed the framework emphasized negative aspects of American History, and short-changed ideals like American exceptionalism. Others have decried the poor results on the NAEP Civics Test as a clear sign of civic illiteracy. On the other side, many educators viewed the events of Ferguson and the Black Lives Matter movement as opportunities to promote civic activism. Should American History and civics classes emphasize civic activism or civic literacy? Most curricula and classrooms will include some of both, and the two emphases are not mutually exclusive. However, the model below helps us understand these two approaches, and evaluate which way the pendulum may be swinging at the national, state, local, and classroom level. Consider the headlines below. What approach to civic education is emphasized? By Matt Doran Skills: What should students be able to do? Apply disciplinary thinking skills to text sets to show the relationship among social studies content, current events, and civic engagement. The use of text sets supports infusion of the Common Core Literacy in History/Social Studies standards, and holds great potential for creating a 21st century social studies classroom. A text set is a collection of readings organized around a common theme or line of inquiry. The anchor text is the focus of a close reading. Supporting texts are connected meaningfully to the anchor text and to each other to deepen student understanding of the anchor text. In social studies, close reading of content texts is not an end in itself, but rather a means to creating successful citizens. In this model, anchor texts can be pulled from rich collections of primary and secondary sources. Supporting texts from current events show the enduring relevance of the themes and questions raised in these readings from history, geography, and government and economics. Applying the tools of disciplinary thinking and common core literacy standards across the text sets prepares students to engage in meaningful civic discourse and take informed action. Here is one example of an inquiry-based text set unit: Course Overarching Essential Question

Unit Compelling Question

Supporting Questions

Text Set Anchor

Supporting

For a complete text lesson, with anticipation guide, adapted readings, and close reading questions, download the resources from this page on Share My Lesson (free account required).  Nineteen years ago, I wrote my high school senior research paper on the conservatism of the American Revolution. I used primary sources to argue, quite cogently for an 18-year-old, that the "American Revolution was a conservative movement aimed at restoring traditional British rights to the American colonists." Apparently, I was relying heavily on Daniel Boorstin and had not read much of Gordon Wood or Bernard Bailyn in high school. So, was the American Revolution radical or conservative? The American Revolutionaries' fight for liberty began as a conservative argument for rights as British subjects. However, the more radical nature of the American Revolution is evident when we look beneath the surface at the new argument Americans used to defend their rights: the higher-law principles of consent of the governed and natural rights. This radicalism, however, was tempered by the failure of the American founders to extend political rights to all those who naturally deserved them. For the British, sovereignty resided with the "King in Parliament." The British government was a hybrid system with medieval elements of a hereditary monarchy and House of Lords. But, it also included a House of Commons, and system of rotten burroughs in which representation was not proportional to population. Although radical Whigs in Britain began to assert the doctrine of consent, most Whigs and Tories had to agree not to address any such principles of higher law because it would require their entire system to be reworked. They agreed to ignore the problem of consent and pretend the Glorious Revolution was just a moment of inconvenience. As Americans agitated for their rights, the British continued to defend their system only on the grounds of customs and traditions of British law. In the "Summary of the View of Rights of British Americans," Thomas Jefferson tried to force the British to deal with the higher-order issue of consent. He blamed the King for failing to act as a negative against Parliament. Jefferson argued that colonial legislatures had equal authority with Parliament and it was the responsibility of the King to use his negative to protect the American colonies. But, of course, there was no such tradition that would allow these kinds of checks. It was only on the basis of higher-law principles of consent that the King could act in such a manner, and the British would not concede a higher law. Edmund Burke recognized the problems inherent in British taxation of the American colonies. He argued that the British government should stop taxing the Americans because it would continue to raise questions about higher-law principles and point out contradictions in the British system. Nonetheless, the British continued to assert the right, through the Declaratory Act, to do as they wished because Parliament was supreme. The Declaration of Independence was the Americans' magnum opus on higher-law rights. The Declaration listed grievances against the King for violations of the rights of colonists, but only after asserting a radical idea for the origins of rights: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness." While the ideals of the Declaration and American Revolution were radical, the political realities were far from matching the rhetoric. Although some states outlawed slavery during and immediately after the American Revolution, the Constitution left in place a system of slavery that denied the most basic natural rights to enslaved African Americans. Frederick Douglass pointed out these contradictions in his 1852 speech, "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?": "Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! ...The blessings in which you this day rejoice are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity, and independence bequeathed by your fathers is shared by you, not by me. ...This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. ..." Abolitionists of the 19th century (along with later women's rights and civil rights leaders) understood that the higher-law principles of the Declaration were the true foundation of freedom and equality. Setting out the aims of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1833, William Garrison called liberty both an inalienable right and a God-given right. To deny another liberty, he reasoned, infringed upon both the “law of nature” and constituted a “presumptuous transgression of all the holy commandments.” He concluded the same manifesto by affirming the movement’s two foundational documents: The Declaration of Independence and the Bible. Garrison was critical of the Constitution for its concessions to slavery, especially the Three-Fifths compromise. He regarded this as a betrayal of both republicanism and Christianity. The Declaration of Independence asserted the high and radical aims of the American Revolution: the Enlightenment principles of consent of the governed and natural rights. But forces of conservatism kept many from enjoying those rights until later generations of radicals led movements for political change. |

Blog Categories

All

Blog Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

3/23/2020

0 Comments