Reflections and Collections for the 21st Century Social Studies Classroom

|

By Matt Doran The impeachment of Andrew Johnson in 1868, as with all of the Reconstruction Era, provides a good lens for the study of historiography—the history of historical writing/interpretations. How have historians answered the question: Was the impeachment of Andrew Johnson’s justified? Early American history texts presented the Johnson impeachment as an outrageous overreach—part of a broader interpretation in the era of Jim Crow that portrayed Reconstruction as too radical. From David Saville Muzzey, A History of Our Country (1943) Not content with reducing President Johnson to political impotence, the radicals were determined to drive him out of the White House. On the same day (March 2, 1867) that it destroyed the President’s governments in the South by the Reconstruction Act, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act, which took from him the privilege, exercised by every President since Washington’s day, of dismissing the members of his own cabinet at his pleasure. It was an outrageous measure, designed merely as a trap to catch Johnson in a “violation” of the law and hence furnish a reason for bringing an accusation against him. When, therefore, the President dismissed his Secretary of War Stanton, who was a virtual spy in the cabinet in close alliance with the radicals in Congress, the House of Representatives impeached Johnson of “high crimes and misdemeanors.” The Senate tried the case from March 30 to May 26, 1868; but in spite of the frantic efforts the radicals to secure a conviction, seven Republican Senators were honorable enough to place justice before partisan hatred and vote with the twelve Democrats for the President’s acquittal, making the vote (35 to 19) fall one short of the two thirds necessary for conviction. By this narrow margin the country was saved from the disgrace of using a clause of the Constitution as a weapon of personal and political vengeance against the highest officer of the land. From Samuel Eliot Morrison, The Oxford History of the American People (1965) The Radical leaders of the Republican party, not content with establishing party ascendancy in the South, aimed at capturing the federal government under the guise of putting the presidency under wraps. By a series of usurpations they intended to make the majority in Congress the ultimate judge of its own powers, and the President a mere chairmen of a cabinet responsible to Congress, as the British cabinet is to the House of Commons. An opening move in this game was the Tenure of Office Act of March 1867 which made it impossible for the President to control his administration, by requiring him to obtain the advice and consent of the Senate for removals as well as appointments to office. The next move to dispose of John by impeachment, so that Radical Ben Wade, president pro-tem of the Senate, would succeed to his office and title. In the wake of the civil rights movement in the 1960s and 1970s, historians challenged traditional Reconstruction interpretations. Writing during the height of the Watergate investigation in 1973, Michael Les Benedict argued that impeachment was a legitimate response to Johnson’s efforts to undermine Reconstruction. From Michael Les Benedict, "The Impeachment Precedent," New York Times (1973) Andrew Johnson, however, was not nearly so innocent a victim. After the war, he arrogated to himself the entire responsibility for restoring civil government in the South—under his inherent war powers as Commander in Chief, he claimed—and denied that Congress had any authority in the premises. . . . Like Benedict, Eric Foner has shown little sympathy for Andrew Johnson in his four decades of writing on Reconstruction. From Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (2010). Andrew Johnson was self-absorbed, insensitive to the opinions of others, unwilling to compromise, and unalterably racist. If anyone was responsible for the downfall of his presidency it was Johnson himself. With Congress out of session until December 1865, Johnson took it upon himself to bring about Reconstruction, establishing new governments in the South in which blacks had no voice whatever. When these governments sought to reduce the freedpeople to a situation reminiscent of slavery, he refused to heed the rising tide of Northern concern or to budge from his policy. As a result, Congress, after attempting to work with the President, felt it had no choice but to sweep aside Johnson's Reconstruction plan and to enact some of the most momentous measures in American history: the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which accorded blacks equality before the law; the 14th Amendment, which put the principle of equality unbounded by race into the Constitution; the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which mandated the establishment of new governments in the South with black men, for the first time in our history, enjoying a share of political power. Johnson did everything in his power to obstruct their implementation in 1868. Fed up with his intransigence and incompetence, the House of Representatives impeached Johnson and he came within one vote of conviction by the Senate. By Matt Doran

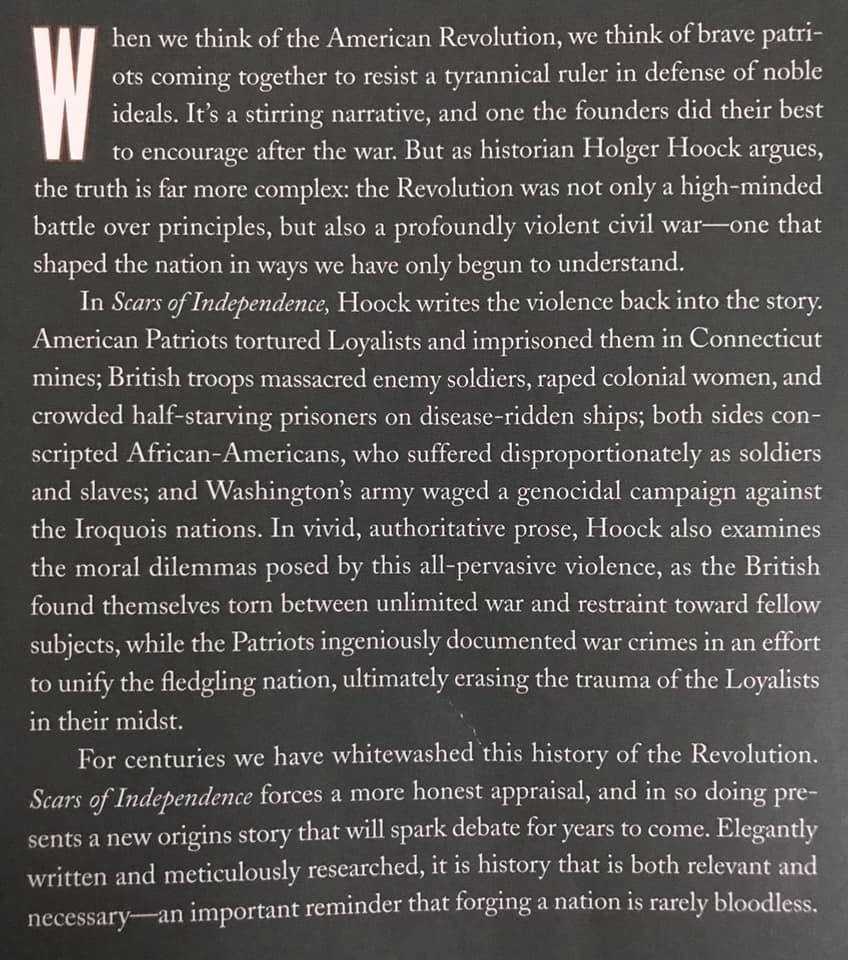

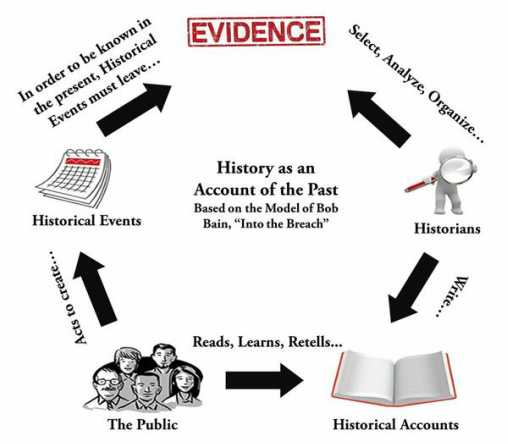

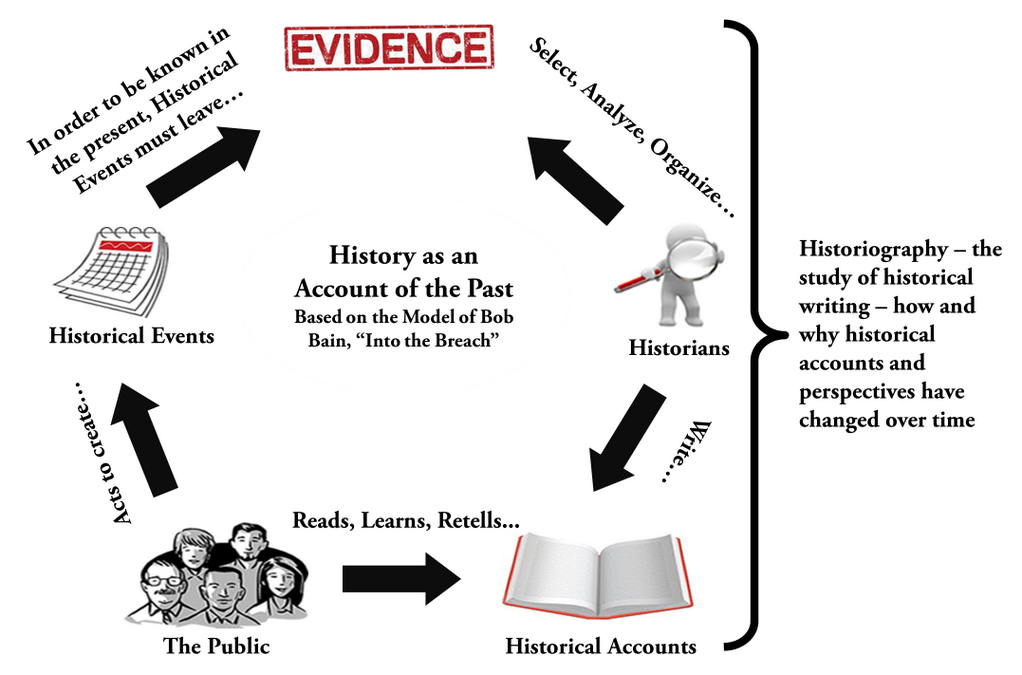

Especially on patriotic holidays, our propensity is to sanctify the causes of our wars. But clear historical analysis compels a more complex and nuanced narrative. The back cover of Scars of Independence: America's Violent Birth by Holger Hoock gives us pause for reflection and analysis.  Nineteen years ago, I wrote my high school senior research paper on the conservatism of the American Revolution. I used primary sources to argue, quite cogently for an 18-year-old, that the "American Revolution was a conservative movement aimed at restoring traditional British rights to the American colonists." Apparently, I was relying heavily on Daniel Boorstin and had not read much of Gordon Wood or Bernard Bailyn in high school. So, was the American Revolution radical or conservative? The American Revolutionaries' fight for liberty began as a conservative argument for rights as British subjects. However, the more radical nature of the American Revolution is evident when we look beneath the surface at the new argument Americans used to defend their rights: the higher-law principles of consent of the governed and natural rights. This radicalism, however, was tempered by the failure of the American founders to extend political rights to all those who naturally deserved them. For the British, sovereignty resided with the "King in Parliament." The British government was a hybrid system with medieval elements of a hereditary monarchy and House of Lords. But, it also included a House of Commons, and system of rotten burroughs in which representation was not proportional to population. Although radical Whigs in Britain began to assert the doctrine of consent, most Whigs and Tories had to agree not to address any such principles of higher law because it would require their entire system to be reworked. They agreed to ignore the problem of consent and pretend the Glorious Revolution was just a moment of inconvenience. As Americans agitated for their rights, the British continued to defend their system only on the grounds of customs and traditions of British law. In the "Summary of the View of Rights of British Americans," Thomas Jefferson tried to force the British to deal with the higher-order issue of consent. He blamed the King for failing to act as a negative against Parliament. Jefferson argued that colonial legislatures had equal authority with Parliament and it was the responsibility of the King to use his negative to protect the American colonies. But, of course, there was no such tradition that would allow these kinds of checks. It was only on the basis of higher-law principles of consent that the King could act in such a manner, and the British would not concede a higher law. Edmund Burke recognized the problems inherent in British taxation of the American colonies. He argued that the British government should stop taxing the Americans because it would continue to raise questions about higher-law principles and point out contradictions in the British system. Nonetheless, the British continued to assert the right, through the Declaratory Act, to do as they wished because Parliament was supreme. The Declaration of Independence was the Americans' magnum opus on higher-law rights. The Declaration listed grievances against the King for violations of the rights of colonists, but only after asserting a radical idea for the origins of rights: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness." While the ideals of the Declaration and American Revolution were radical, the political realities were far from matching the rhetoric. Although some states outlawed slavery during and immediately after the American Revolution, the Constitution left in place a system of slavery that denied the most basic natural rights to enslaved African Americans. Frederick Douglass pointed out these contradictions in his 1852 speech, "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?": "Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! ...The blessings in which you this day rejoice are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity, and independence bequeathed by your fathers is shared by you, not by me. ...This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. ..." Abolitionists of the 19th century (along with later women's rights and civil rights leaders) understood that the higher-law principles of the Declaration were the true foundation of freedom and equality. Setting out the aims of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1833, William Garrison called liberty both an inalienable right and a God-given right. To deny another liberty, he reasoned, infringed upon both the “law of nature” and constituted a “presumptuous transgression of all the holy commandments.” He concluded the same manifesto by affirming the movement’s two foundational documents: The Declaration of Independence and the Bible. Garrison was critical of the Constitution for its concessions to slavery, especially the Three-Fifths compromise. He regarded this as a betrayal of both republicanism and Christianity. The Declaration of Independence asserted the high and radical aims of the American Revolution: the Enlightenment principles of consent of the governed and natural rights. But forces of conservatism kept many from enjoying those rights until later generations of radicals led movements for political change. By Matt Doran Skills: What do we want students (citizens) to able to do? Critically analyze perspectives in secondary sources, situating these sources in their social and political context to determine factors that shape historians’ perspectives on the past. "Each age tries to form its own conception of the past. Each age writes the history of the past anew with reference to the conditions uppermost in its own time." - Frederick Jackson Turner Thomas Jefferson: apostle of agrarian democracy? Champion of the rights of the common people? Enlightenment skeptic? Liberal capitalist? Southern aristocrat? Racist? Suppressor of civil liberties? These were among the historiographical questions that shaped an undergraduate course I took called Jeffersonian and Jacksonian Democracy. I had been introduced to historiography a year earlier, in “Introduction to Historical Thought,” a gateway course to the history major. Historiography is the study of historical writing—examining the history of historical perspectives with attention to the social and political context of each generation (or school) of historians. Historiography considers why and how history changes over time. I learned about historiography in other courses as well, but in Jeffersonian and Jacksonian Democracy we did historiography. We looked at Jefferson and Jackson through a critical analysis of secondary sources, using a three-pronged heuristic adapted from Robert Berkhofer’s “Demystifying Historical Authority” 1. What is the surface meaning? 2. What could have been said, but wasn’t? 3. What intellectual underpinnings shape the historian’s perspective? But, that was college…and an upper-level undergraduate class…for history majors. Can secondary social studies teachers employ a similar approach? In Teaching What Really Happened, James Loewen’s answer is a definitive “yes.” In fact, Loewen has introduced historiography to students as young as fourth grade, noting that “if they can learn supercalifragilisticexpialidocious, they can handle historiography.” As a high school teacher, I incorporated some elements of historiography into instruction. We looked at various textbook titles and covers from American history textbooks of different eras. What does the title Two Centuries of Progress (1978) imply? Is there a difference between Rise of the American Nation (1977) and Out of Many: A History of the American People (2001)? What change in front material do you notice in textbooks published shortly after 2001? (inclusion of patriotic inserts such as the Pledge of Allegiance) How did changing social and political concerns influence these titles? We also looked at various interpretations of the American Revolution, the Early Republic and the Civil War and Reconstruction—mostly with me explaining those views. What I did not establish, however, was a comprehensive approach that required students to do historiography consistently throughout the year. Since leaving the classroom for full-time curriculum and professional development work, I have gathered a set of resources and developed strategies and tools fordoing historiography in the secondary classroom. A Conceptual Framework of History Before students dig into historiography, they need to be grounded in an understanding of the nature of history. Bob Bain’s conceptual model from “Into the Breach” is one method for introducing the discipline of history. The adaptation below shows the relationship between past events, evidence, historians, and historical accounts. Once students are comfortable with this model of history, teachers can add the historiography layer. Getting Started with Historiography As with other challenging social studies concepts, the best starting point is to access students’ prior knowledge and build on what they already know. Rather than starting with Jefferson and Jackson, look first at popular examples that relate to students lives more directly. For example, how did sportswriters in Cleveland interpret LeBron James in 2003? in 2011? in 2014? Was he viewed as a hero or villain? How did the changing context (the changing teams) shape their interpretation of James? (See the video link here for Kyle Ward’s Brett Favre analogy). Just as our perspectives on the present are shaped by our worldview (and personal loyalties), historians’ view the past through the lens of contemporary concerns and ideologies. As a transition from popular examples to historical perspectives, have students work in groups to summarize and evaluate some of the following quotes that illustrate the concept of historiography:

Unpacking Secondary Sources Historians do not limit their investigation of evidence to primary sources. They also read what other historians have written and how those historians used their evidence. Students should do this as well. As Joe Sangillo, Social Studies Curriculum Specialist with Montgomery County Schools, tweets: If you need a rationale for incorporating historiography and secondary source analysis, note the following Common Core Literacy in History/Social Studies Standards:

James Loewen suggests ten questions that can be applied to a variety of secondary sources (historic site, documentary film, textbook, etc.)

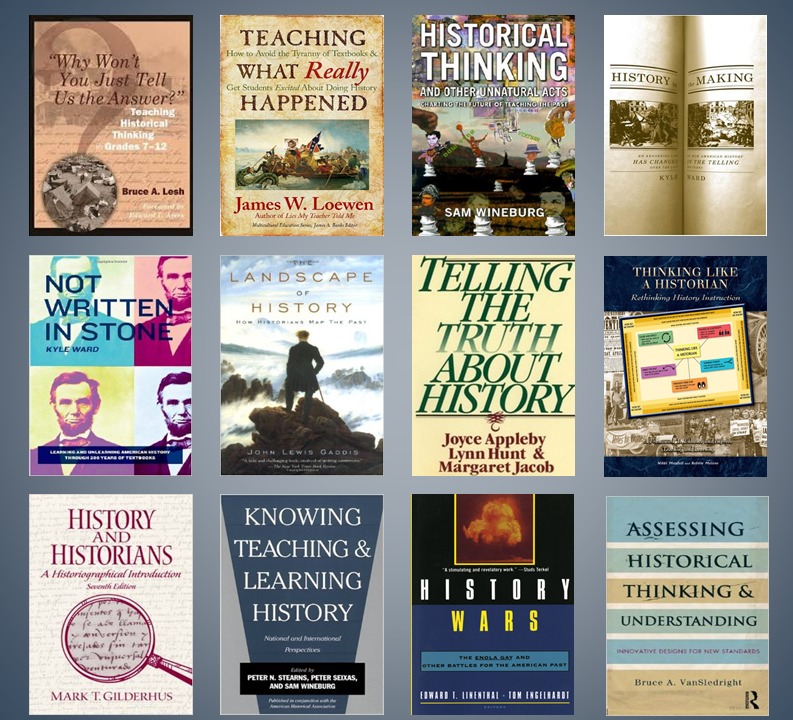

See James Loewen, Teaching What Really Happened: How to Avoid the Tyranny of Textbooks and Get Students Excited About Doing History Again, starting with relevant and accessible examples will help students learn the work of historiography before ultimately moving on to more complex historical monographs. Consider some of the strategies below. Nostalgia Sitcoms View episodes of nostalgia sitcoms such as Happy Days, Wonder Years, or The Goldbergs. These shows are set in an earlier historical period. Happy Days, (1974-1984), presents an interpretation of life in the 1950s. What interpretation of the 1950s is portrayed? (hint: consider the show’s title). What aspects of the 1950s are left out? (hint: see Michael Harrington’s The Other America). What social and political conditions in the late 1970s might have caused the producers and the American public to long for a happier era? The Wonder Years (1988-1993) portrays life in the late 1960s and early 1970s—tackling issues like the Vietnam War, counterculture movement, and the cultural divide between generations. Who might have been the target audience for this show? What cultural and economic trends in the 1990s may have influenced the writers’ decision to point out some of the turbulent aspects of the 1960s and 1970s? Historic Markers Choose an historic marker in the neighborhood and analyze the narrative presented on the marker. Loewen argues that every historic marker is “a tale of two eras: what it’s about and when it went up.” In other words, the historical narrative presented reflects the social and political context in which the marker was created, and the beliefs and values of the sponsoring organization. Loewen documents examples of these markers in Lies Across America: What Our Historic Sites Get Wrong. Loewen’s suggested questions above are helpful for analyzing marker texts. Textbooks Instead of abandoning textbooks altogether, we should consider new ways of using them. Textbooks can be artifacts for analysis. Rather than looking at the text as an authority from which to glean truth, an historiographical approach requires students to ask questions about what is and is not included in a text, how various events and individuals are portrayed, what visuals are chosen to supplement the narrative, etc. Bob Bain offers a step-by-step approach for questioning textbook authority:

Kyle Ward’s book, History in the Making presents textbook excerpts from 200 years of American history, looking at how interpretations of familiar historical events have changed over time. Not Written in Stone offers an abridged and annotated version History in the Making designed for classroom use. In each section, Ward provides an overview and questions for discussions for each set of excerpts. Students can use the graphic organizer linked here to analyze these excerpts and other secondary accounts. Assessments and Additional Resources The Stanford History Education Group’s Beyond the Bubble: History Assessments of Thinking work well for assessing students’ skills in historiography. The John Brown’s Legacy assessment asks students to examine a poster for a play written in 1936 that celebrates the abolitionist John Brown. Students must situate the playbill in time, understanding how the anti-lynching campaign of the 1930s and the rise of fascism in Germany may have motivated the authors to write a play as a commentary on racism. A similar assessment on Creating Columbus Day (during the Gilded Age) asks why President Harrison declared Columbus Day a national holiday in 1892. Students should explain that Harrison’s decision might have been a calculated move to court Catholic voters in the upcoming election. Russel Tarr’s Active History website offers a collection of resources on historiography designed for use in IB History, but adaptable for other secondary history classrooms. The resources include lectures on various theories of historical causation, student activities, and a historiographical terms handout. See the video clips and book titles below for additional resources on historiography. Teaching students to do historiography in the secondary classroom is not an easy task. However, with the right resources, tools, and scaffolds it is an achievable task. As Loewen notes, “historiography is one of the great gifts that history teachers can bestow upon their students.” I welcome your thoughts on how we can work to bestow this gift to students. |

Blog Categories

All

Blog Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

9/25/2019

0 Comments