Reflections and Collections for the 21st Century Social Studies Classroom

|

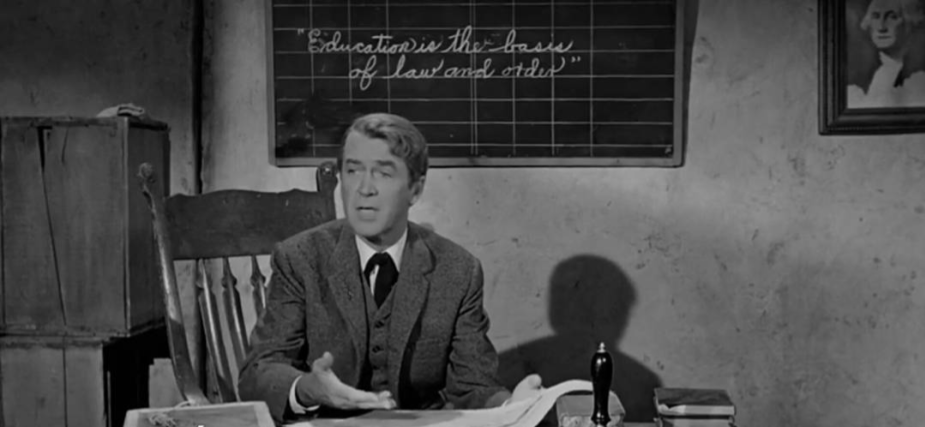

By Matt Doran Dispositions: 3) What do we want students (citizens) to value? Appreciate the importance of literacy and civic education in the success of the American republic. It’s back to school week for many teachers and students—a good time to remind ourselves of the purpose of public education. In recent years, many schools have adopted STEM-focused programs and career pathways mission statements. To be sure, these are good and necessary aspects of a well-rounded education. We should not, however, allow these emphases to distract us from the fundamental civic mission of education in the United States – a mission deeply rooted in the history of the American republic. Thomas Jefferson believed that education and civic virtue must go hand in hand-in-hand in a successful republic. By teaching citizens of their right to self-government, education serves as the guardian of democracy. Noting the historical propensity for governments to be “perverted into tyranny,” Jefferson argued that knowledge of this history was the best safeguard against it. Moreover, liberal education was necessary for leaders who would “guard the sacred deposit of the rights and liberties of their fellow citizens….” In his “Report of the Commissioners Appointed to Fix the Site of the University of Virginia, 1818” Jefferson further outlined the civic purposes of education—improving morals through reading, understanding duties and rights, and exercising of sound judgment. To accomplish these ends, citizen students should learn reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, history, the principles of government, and perhaps most importantly, “a sound spirit of legislation, which…shall leave us free to do whatever does not violate the equal rights of another…” Fast forward to the second half of the 20th century. The U.S. and Soviet Union were engaged in a Cold War “space race” that stimulated an increased emphasis (and funding) on science and math education in the United States. At the height of the Cold War in 1962, producer John Ford reminded his viewers of the civic mission of education in his Western film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. The film’s main character, Ransom Stoddard (played by Jimmy Stewart), established a school in the “uncivilized” town of Shinbone to teach literacy and Enlightenment principles of American self-government. The classroom chalkboard revealed Stoddard’s Jeffersonian vision of education and citizenship: “Education is the basis of law and order”—emphasizing both the instrumental purpose of education and the order of operations. Education must come first, for it teaches citizens that they are rational people, entitled to have liberty and self-government, capable of maintaining it, and willing to do so for the good of the community. Education emerged in response to the need for a virtuous citizenry that could create a civilized society by establishing law and order and removing the obstacles to it. Stoddard’s pupils learned that they have a republic, which one immigrant woman defined as “the people are the boss… If the people in Washington don’t do what we want, we vote them out.” Governing power rests with the electorate who exercise their power through the vote, Stoddard explained. To help his pupils apply their understanding of self-government and the power of the vote, Stoddard used a newspaper article that outlined the potential impact of the cattle ranchers’ efforts to fight statehood. The consequences would be the loss of local control and small shops, and a way of life for these small communities. This effort could only be stopped by the power of the electorate. In doing so, they would also stop Liberty Valance who worked as the ranchers’ lead ruffian. While Valance terrorized the town, Shinbone’s duty constituted law and order, Marshal Appleyard, was paralyzed by fear. He showed no interest in education and, consequently, did nothing to guard the safety of the community. He had no intrinsic understanding of self-government—its historical and philosophical basis— and why this is worth preserving. In short, he was uneducated. Once armed with education, Shinbone’s citizens could select delegates to the legislature, resist the efforts of the big ranchers to block statehood, and render Liberty Valance obsolete. In this present world of 21st century learning, we should not lose sight of the historical centrality of civic education in America. According to one story, Benjamin Franklin, upon leaving the Constitutional Convention, was asked what sort of government the delegates had created. His answer: “A republic, if you can keep it.” Indeed, successful republics—both then and now—demand not only the consent of the people, but also the education and active engagement of its citizens. By Matt Doran

Dispositions: 3) What do we want students (citizens) to value? A deep and broad understanding of the human experience—to become better citizens, and better human beings, who make the world a better place. If 21st century learning is about inquiry, problem-solving and real-world application of academic content, then interdisciplinary teaching and learning are essential. Rarely are the significant issues in our world addressed through a single disciplinary lens. The field of social studies is inherently interdisciplinary—combining the lenses of history, geography, political science, sociology, economics, and the arts. Adding the richness of language, literature, and composition through English classes can further enhance the interdisciplinary humanities learning experience. Traditionally, interdisciplinary social studies/English classes have utilized one of two approaches. The chronological approach largely follows the history curriculum and ties in literature from the historical period. This typically results in greater disruption for the English curriculum, as new readings are added, old ones subtracted, and others shifted to different times of the year. Alternatively, the thematic approach moves away from chronology and pulls together various literature selections and historical episodes organized around a set of themes. In this approach, both social studies and English curricula require an overhaul. Is there an alternative approach? How can schools use an interdisciplinary approach without immediately revamping the entire English or social studies curricula and writing something from scratch? Are there themes that can be used to link the courses together, again without radically revamping either? What small steps can teachers take to make both courses more related, and ultimately more meaningful? Following the principles of backward design can help teachers plan interdisciplinary English and social studies. In backward design, teacher-planners focus first on the macro-curriculum, then begin filling in the weekly details (micro-curriculum) from the big ideas, enduring understandings, and essential questions of the course. 10,000-Foot View: The Purpose of Humanities To start macro-planning, begin with the most fundamental question of the disciplines. What is the purpose of this course? In Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts, Sam Wineburg presents a succinct view of the purpose of the humanities: “What is history good for? Why even teach it in schools? My claim in a nutshell is that history holds the potential, only partly realized, of humanizing us in ways offered by few other areas in the school curriculum. … Each generation must ask itself anew why studying the past is important, and remind itself why history can bring us together rather than—as we have seen most recently—tear us apart.” Wineburg’s quote reminds us why we teach social studies and English: to deepen and broaden students’ understanding of the human experience. We teach humanities to help students become better citizens, and better human beings, who make the world a better place. Students come to recognize the unity of humanity, but respect diversity and value different points-of-view. They learn to empathize with people, past and present, near and far. They learn critical analysis, reasoned judgment, argumentation and deliberation, and how to apply the lessons of the past to contemporary issues. The humanities disciplines remind us the STEM education is necessary, but not sufficient. Solving the world’s grand problems is not only a matter of engineering design or scientific discovery, but must also take into consideration aesthetics, culture, history, and ethics. 1,000-Foot View: Establishing Themes – Big Ideas, Enduring Understandings, Essential Questions The major themes of the course (the big ideas) should flow from the purpose of the course. What themes will help deepen students’ understanding of the human experience? Look for themes that are broad enough to cut across multiple historical eras and wide array of literature. Some existing frameworks may be helpful guides for establishing course themes. Colonial Williamsburg’s The Idea of America, frames American studies through the lens of four value tensions:

For more of a social justice approach, consider the four domains of the Teaching Tolerance anti-bias framework:

Another approach is to create themes that reflect the various disciplinary lenses of the course, such as:

The themes of the course will drive the enduring understandings and essential questions. Think of an enduring understanding as the “moral of the story.” These are statements that not only summarize the key ideas of the discipline, but are transferrable to other disciplines and to the real world—having long-term value beyond the classroom. For example, using the value tension of law vs. ethics, an enduring understanding might be framed as:

For the theme of identity, an enduring understanding could read:

An enduring understanding using the theme of power could be:

Essential questions are critical to creating an inquiry-based environment. Essential questions should be provocative, open ended and arguable. These should not be questions with a simple or straightforward correct answer. Rather, they are designed to provoke further inquiry, debate, and deliberation. Here are a few examples that follow from the enduring understandings above:

100-Foot View: Selecting Resources and Tracking the Themes Once the course purpose, themes, enduring understandings and essential questions have been established, the micro-planning may begin. This is the phase that involves the selection and order of readings, projects, and assignments. With broad and meaningful course themes, teachers may find that many of the resources in their current portfolio simply need some tweaking or re-organization to work into the interdisciplinary macro-plan. It many cases, pairing course materials with course themes may be more a matter of the emphasis within particular resources, rather than the selection of all new ones. It is important to keep in mind that course themes can be utilized in a chronological, thematic, or hybrid framework. It is not necessary to cover the themes individually as separate units, though this is one possible means of organization. If a chronological or hybrid approach is preferred, the course themes, enduring understandings, and essential questions can be introduced early on and reinforced throughout the year. Consider creating large posters on the classroom walls for each theme and adding to those posters throughout the course. Students could also track the themes in a journal or develop a set of theme-based notecards throughout the course. Interdisciplinary writing tasks can also be an effective tool for linking both English and social studies courses to the broader course themes. Here are some prompt possibilities:

Interdisciplinary teaching is not an easy task, but it is an achievable task that can be greatly enhanced by a focus on backward design and macro-planning. Here is another piece of good news. The National Humanities Center has already created an excellent set of lessons and primary source collections using this approach, all of which are available for free online at: http://americainclass.org/primary-sources/ and http://americainclass.org/lessons/. Finally, here are some thoughts gathered from my Facebook friends, all veteran humanities teachers of social studies and English. |

Blog Categories

All

Blog Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

8/15/2014

0 Comments