Reflections and Collections for the 21st Century Social Studies Classroom

|

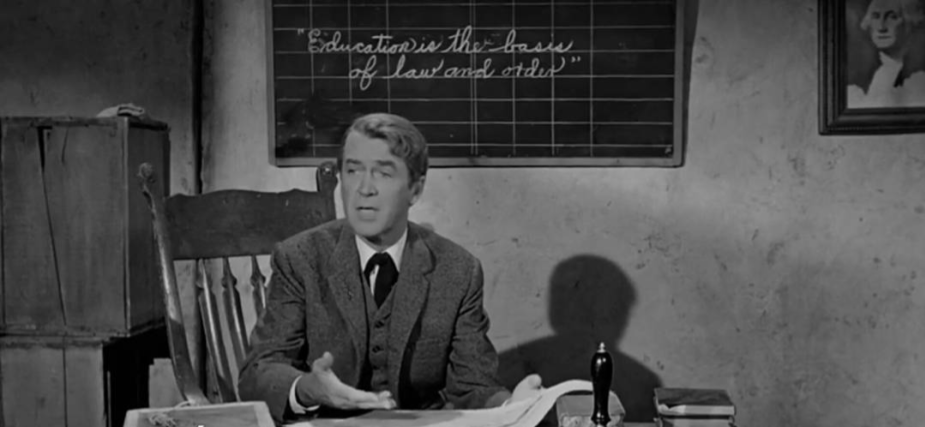

By Matt Doran Dispositions: 3) What do we want students (citizens) to value? Appreciate the importance of literacy and civic education in the success of the American republic. It’s back to school week for many teachers and students—a good time to remind ourselves of the purpose of public education. In recent years, many schools have adopted STEM-focused programs and career pathways mission statements. To be sure, these are good and necessary aspects of a well-rounded education. We should not, however, allow these emphases to distract us from the fundamental civic mission of education in the United States – a mission deeply rooted in the history of the American republic. Thomas Jefferson believed that education and civic virtue must go hand in hand-in-hand in a successful republic. By teaching citizens of their right to self-government, education serves as the guardian of democracy. Noting the historical propensity for governments to be “perverted into tyranny,” Jefferson argued that knowledge of this history was the best safeguard against it. Moreover, liberal education was necessary for leaders who would “guard the sacred deposit of the rights and liberties of their fellow citizens….” In his “Report of the Commissioners Appointed to Fix the Site of the University of Virginia, 1818” Jefferson further outlined the civic purposes of education—improving morals through reading, understanding duties and rights, and exercising of sound judgment. To accomplish these ends, citizen students should learn reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, history, the principles of government, and perhaps most importantly, “a sound spirit of legislation, which…shall leave us free to do whatever does not violate the equal rights of another…” Fast forward to the second half of the 20th century. The U.S. and Soviet Union were engaged in a Cold War “space race” that stimulated an increased emphasis (and funding) on science and math education in the United States. At the height of the Cold War in 1962, producer John Ford reminded his viewers of the civic mission of education in his Western film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. The film’s main character, Ransom Stoddard (played by Jimmy Stewart), established a school in the “uncivilized” town of Shinbone to teach literacy and Enlightenment principles of American self-government. The classroom chalkboard revealed Stoddard’s Jeffersonian vision of education and citizenship: “Education is the basis of law and order”—emphasizing both the instrumental purpose of education and the order of operations. Education must come first, for it teaches citizens that they are rational people, entitled to have liberty and self-government, capable of maintaining it, and willing to do so for the good of the community. Education emerged in response to the need for a virtuous citizenry that could create a civilized society by establishing law and order and removing the obstacles to it. Stoddard’s pupils learned that they have a republic, which one immigrant woman defined as “the people are the boss… If the people in Washington don’t do what we want, we vote them out.” Governing power rests with the electorate who exercise their power through the vote, Stoddard explained. To help his pupils apply their understanding of self-government and the power of the vote, Stoddard used a newspaper article that outlined the potential impact of the cattle ranchers’ efforts to fight statehood. The consequences would be the loss of local control and small shops, and a way of life for these small communities. This effort could only be stopped by the power of the electorate. In doing so, they would also stop Liberty Valance who worked as the ranchers’ lead ruffian. While Valance terrorized the town, Shinbone’s duty constituted law and order, Marshal Appleyard, was paralyzed by fear. He showed no interest in education and, consequently, did nothing to guard the safety of the community. He had no intrinsic understanding of self-government—its historical and philosophical basis— and why this is worth preserving. In short, he was uneducated. Once armed with education, Shinbone’s citizens could select delegates to the legislature, resist the efforts of the big ranchers to block statehood, and render Liberty Valance obsolete. In this present world of 21st century learning, we should not lose sight of the historical centrality of civic education in America. According to one story, Benjamin Franklin, upon leaving the Constitutional Convention, was asked what sort of government the delegates had created. His answer: “A republic, if you can keep it.” Indeed, successful republics—both then and now—demand not only the consent of the people, but also the education and active engagement of its citizens. Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Blog Categories

All

Blog Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

8/15/2014

0 Comments