Reflections and Collections for the 21st Century Social Studies Classroom

|

By Matt Doran The impeachment of Andrew Johnson in 1868, as with all of the Reconstruction Era, provides a good lens for the study of historiography—the history of historical writing/interpretations. How have historians answered the question: Was the impeachment of Andrew Johnson’s justified? Early American history texts presented the Johnson impeachment as an outrageous overreach—part of a broader interpretation in the era of Jim Crow that portrayed Reconstruction as too radical. From David Saville Muzzey, A History of Our Country (1943) Not content with reducing President Johnson to political impotence, the radicals were determined to drive him out of the White House. On the same day (March 2, 1867) that it destroyed the President’s governments in the South by the Reconstruction Act, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act, which took from him the privilege, exercised by every President since Washington’s day, of dismissing the members of his own cabinet at his pleasure. It was an outrageous measure, designed merely as a trap to catch Johnson in a “violation” of the law and hence furnish a reason for bringing an accusation against him. When, therefore, the President dismissed his Secretary of War Stanton, who was a virtual spy in the cabinet in close alliance with the radicals in Congress, the House of Representatives impeached Johnson of “high crimes and misdemeanors.” The Senate tried the case from March 30 to May 26, 1868; but in spite of the frantic efforts the radicals to secure a conviction, seven Republican Senators were honorable enough to place justice before partisan hatred and vote with the twelve Democrats for the President’s acquittal, making the vote (35 to 19) fall one short of the two thirds necessary for conviction. By this narrow margin the country was saved from the disgrace of using a clause of the Constitution as a weapon of personal and political vengeance against the highest officer of the land. From Samuel Eliot Morrison, The Oxford History of the American People (1965) The Radical leaders of the Republican party, not content with establishing party ascendancy in the South, aimed at capturing the federal government under the guise of putting the presidency under wraps. By a series of usurpations they intended to make the majority in Congress the ultimate judge of its own powers, and the President a mere chairmen of a cabinet responsible to Congress, as the British cabinet is to the House of Commons. An opening move in this game was the Tenure of Office Act of March 1867 which made it impossible for the President to control his administration, by requiring him to obtain the advice and consent of the Senate for removals as well as appointments to office. The next move to dispose of John by impeachment, so that Radical Ben Wade, president pro-tem of the Senate, would succeed to his office and title. In the wake of the civil rights movement in the 1960s and 1970s, historians challenged traditional Reconstruction interpretations. Writing during the height of the Watergate investigation in 1973, Michael Les Benedict argued that impeachment was a legitimate response to Johnson’s efforts to undermine Reconstruction. From Michael Les Benedict, "The Impeachment Precedent," New York Times (1973) Andrew Johnson, however, was not nearly so innocent a victim. After the war, he arrogated to himself the entire responsibility for restoring civil government in the South—under his inherent war powers as Commander in Chief, he claimed—and denied that Congress had any authority in the premises. . . . Like Benedict, Eric Foner has shown little sympathy for Andrew Johnson in his four decades of writing on Reconstruction. From Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (2010). Andrew Johnson was self-absorbed, insensitive to the opinions of others, unwilling to compromise, and unalterably racist. If anyone was responsible for the downfall of his presidency it was Johnson himself. With Congress out of session until December 1865, Johnson took it upon himself to bring about Reconstruction, establishing new governments in the South in which blacks had no voice whatever. When these governments sought to reduce the freedpeople to a situation reminiscent of slavery, he refused to heed the rising tide of Northern concern or to budge from his policy. As a result, Congress, after attempting to work with the President, felt it had no choice but to sweep aside Johnson's Reconstruction plan and to enact some of the most momentous measures in American history: the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which accorded blacks equality before the law; the 14th Amendment, which put the principle of equality unbounded by race into the Constitution; the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which mandated the establishment of new governments in the South with black men, for the first time in our history, enjoying a share of political power. Johnson did everything in his power to obstruct their implementation in 1868. Fed up with his intransigence and incompetence, the House of Representatives impeached Johnson and he came within one vote of conviction by the Senate. by Matt Doran

If we want to find enduring relevance in education, we must draw from the deep cultural foundations of history and philosophy, not economic and business principles. Education is a social institution with a civic mission. It's not enough to define what we want students to know and be able to do. We must also wrestle with the question: What do we want to students to value? College and Career Readiness is a necessary, but not a sufficient mission for schools. A more comprehensive vision needs to include College, Career, and Civic Life Readiness. The Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools defines civic dispositions as a concern for others' rights and welfare, fairness, reasonable levels of trust, and a sense of public duty. Civic dispositions are crucial to democratic character formation, and the sustainability and improvement of constitutional democracy. If standards must drive our work, then we need a set of civic anchor standards to match those that define critical knowledge and skills. One good option is to pair some of the indicators from the C3 Framework with the Social Justice Standards from Teaching Tolerance. From the C3 Framework: Dimension 2. Civics: Participation and Deliberation: Applying Civic Virtues and Democratic Principles

Dimension 4. Taking Informed Action

From the Teaching Tolerance Social Justice Standards: Identity Anchor Standards

Diversity Anchor Standards

Justice Anchor Standards

Action Anchor Standards

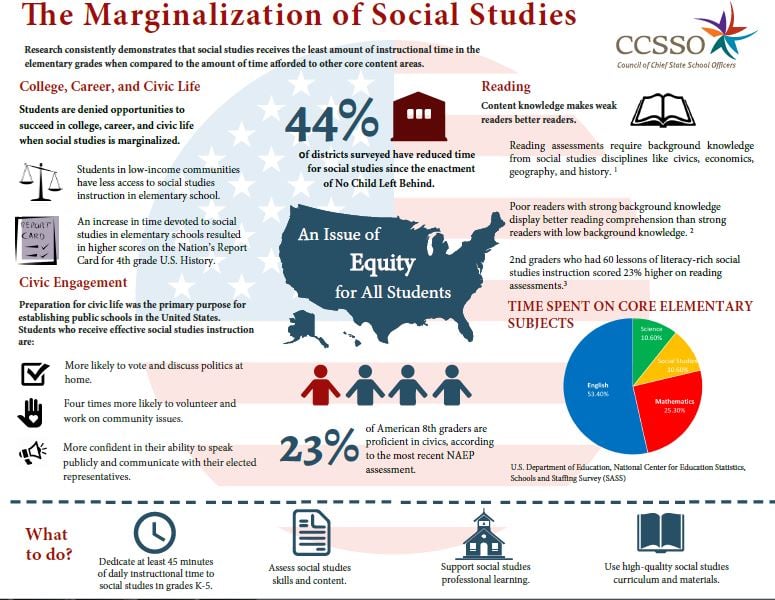

By Matt Doran Those who believe the directive to focus on literacy requires less attention to social studies have failed to understand literacy or social studies. It is true that reading skills help students in other content areas. But the converse is also true: A content-rich curriculum provides the necessary vocabulary and context for successful reading comprehension. The Council of Chief State School Officers has summarized the importance of social studies in the elementary grades. Nell Duke, Professor of Education at the University of Michigan, explains the importance of teaching Social Studies and Science in the elementary grades. |

Blog Categories

All

Blog Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

9/25/2019

0 Comments