Reflections and Collections for the 21st Century Social Studies Classroom

|

By Matt Doran

What can you do to continue the learning at home during the extended school closure? If you are a social studies teacher or interested parent, you really don’t need the latest temporarily-free app. Instead, pose these three questions:

Watch/read the news and write a daily journal reflection on these questions. When the crisis is over, you will have created a new primary source about this event. Then, go back through history and make connections and comparisons across time and place. Here is a historical look at question 3 since 1958 from the Pew Research Center: Public Trust in Government: 1958-2019. Your students will learn way more from this exercise than filling out digital worksheets. 7/18/2019 On Cognitive DissonanceBy Matt Doran My social media posts typically fall well behind the news cycle (if they even make to publication). Rather than retweeting and linking to articles about the issue du jour, I try to use social media platforms in educative ways that promote contemplation and reflection. One question many have recently asked: How is it that seemingly decent people justify and rationalize fundamentally deplorable policies and leaders? The psychological phenomenon of cognitive dissonance helps us understand why individuals will often "explain away" the indefensible. Cognitive dissonance refers the mental discomfort that results from contradictory beliefs, or when our beliefs run contrary to our behaviors (especially in light of new evidence). We seek consistency in our attitudes and perceptions. When what we believe is challenged, something must change in order to reduce the dissonance (lack of agreement). The need for dissonance reduction is especially acute when it involves beliefs about the self. Everyone wants to believe they are fundamentally good people who make good decisions (about health, finances, politics, etc). But sometimes the evidence mounts against us. In government and politics, this happens when parties and leaders engage in actions and policies that violate clear moral and ethical boundaries. To reduce the dissonance, supporters must change a belief--either I'm not so good at making decisions after all, or the actions/policies are justified. Aesop's fable, the Fox and the Grapes, helps illustrate cognitive dissonance. The Fox noticed a beautiful bunch of ripe grapes hanging from a high vine. After multiple attempts to jump for the grapes, the Fox fell short. He finally concludes that the sour grapes are not worth it after all. Clearly, the Fox believed two things: the grapes are desirable and he had the ability to reach them. But when the evidence showed the falsity of his belief about himself, the Fox reduces the dissonance by rationalizing that the grapes really aren't so desirable. Here's a good explanation of cognitive dissonance: https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-cognitive-dissonance-2795012 7/11/2019 Wineburg on Media LiteracyFrom Why Learn History (When It's Already on Your Phone) by Sam Wineburg. "Wedging a media literacy course into an already crammed curriculum is like slapping a new coat of paint on a house that's teetering on its foundation: it lends to better street appeal but it does little to address the underlying problem. Making headway will entail more than a four-week media or news literacy course. It will require a fundamental reorientation to the curriculum. . . . What once fell on the shoulders of editors, publishers, librarians, and subject matter experts now falls on the shoulders of each and every one of us. The big problem with this new reality is that the ill-informed hold just as much power at the polling station as the well-informed. Reliable information is to civic intelligence what clean air and water are to public health. . . . Jefferson's solution is no less apt today than it was in his era. 'If we think [the people] are not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not take it from them, but to inform their discretion by education.'" - Sam Wineburg By Matt Doran

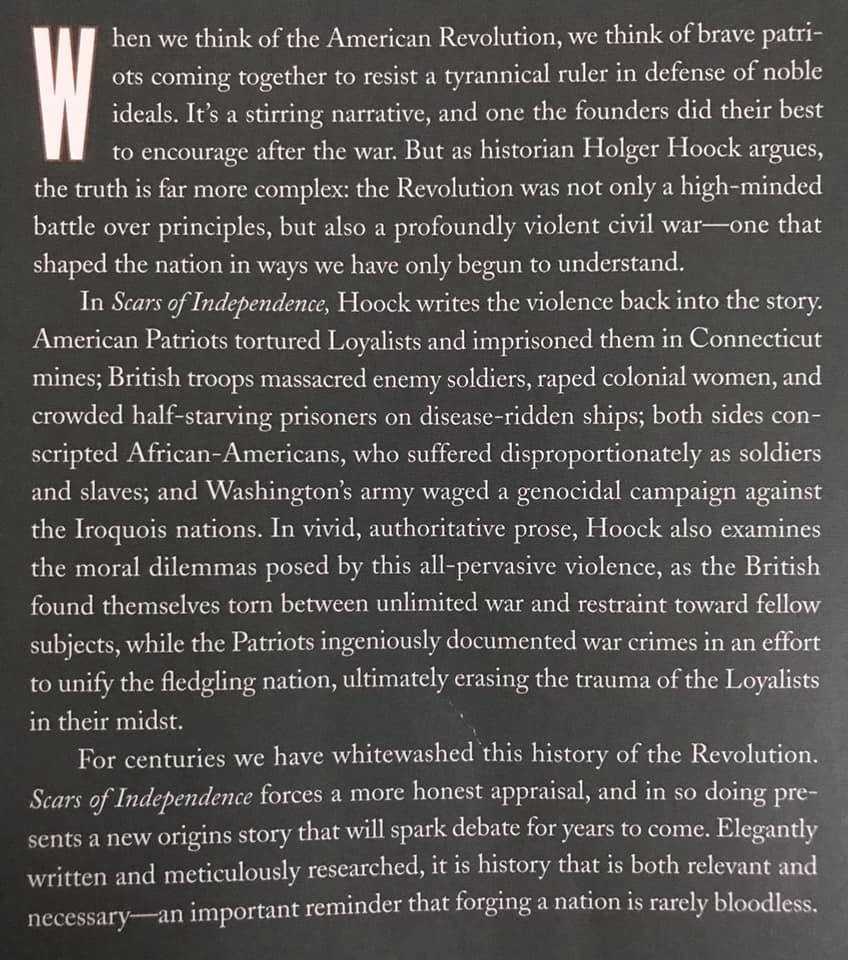

Especially on patriotic holidays, our propensity is to sanctify the causes of our wars. But clear historical analysis compels a more complex and nuanced narrative. The back cover of Scars of Independence: America's Violent Birth by Holger Hoock gives us pause for reflection and analysis. by Matt Doran

This month we began year three of our middle school professional development program, with an emphasis on pedagogical content knowledge. We are focusing our discussions on creating and implementing a vision for social studies in alignment with the C3 Framework. Since social studies is not a state-tested subject in Ohio middle schools, there is often a perception that it is the least important of the core subjects. Balderdash. The opposite is true: Social studies is too important to force into the constraints of state testing. Free from the yoke of testing, middle school social studies teachers have the freedom and flexibility to execute a vision of social studies education that aligns with both the original intent of social studies and its vital purpose in 21st century democracies. The skills, reasoning capacities, and civic dispositions social studies cultivates cannot be effectively captured through a standardized test. The centrality of social studies among the school subjects lies not in its place within the cesspool of corporate testing and sham accountability systems, but in its instrumental purpose in modern democracies. As conceived by the Report of the Social Studies Committee in 1916, social studies is a discipline designed to actualize a Deweyan vision of pragmatism in education. Drawing from a wide-range of disciplines in the humanities and social sciences, social studies aims to tap into students’ interests and use inquiry-learning to solve real-world problems. Its purpose is explicitly instrumental: to improve society. Having emerged in the Progressive Era, the creation of the social studies in school curricula was part of a broader response to the ills and excesses of Gilded Age industrial capitalism. The Progressive Era ushered in democratic reforms in states (referendum, initiative, recall) and the U.S. Constitution (17th and 19th amendments). Laws were passed to safeguard food production and the environment, limit the power of corporate trusts and monopolies, and establish compulsory public education. In the decades since the Progressive Era, historians and social scientists of the various disciplines that make-up social studies have defined thinking skills central to the disciplines. Such skills include conducting original research, contextualizing historical sources, creating and analyzing data sets, evaluating sources, supporting arguments with evidence, and unpacking cause-and-effect relationships. Many scholars today argue that we are living in a Second Gilded Age, defined by social and economic inequality and political corruption. Even if one doesn’t agree with this characterization of our present times, it is difficult to imagine a case being made against the critical importance of social studies in the 21st century. Do we need increased civic engagement, better civil discourse, more cultural awareness, heightened concern for social justice, greater discernment in evaluating the credibility of information, creative cross-disciplinary solutions to real-world problems, and sharper ethical thinking skills? If so, then we need more social studies, not less. As Natalie Wexler has written in a recent Forbes article, “We know that only a minority of students will end up working in STEM fields. But virtually all will be expected to exercise their rights and responsibilities as citizens of a democracy.” With great freedom comes great responsibility. As social studies teachers, we bear the responsibilities of communicating the importance of our vision to the broader community, and designing and aligning our curriculum to meet this instrumental purpose. We cannot decry state testing on the one hand, while continuing to pack our non-tested courses with a superfluity of Googleable names, dates, and facts on the other. In Why Learn History, When It’s Already on Your Phone, Sam Wineburg describes the ongoing work of the Stanford History Education Group to “change history class from a forced march through an all-knowing textbook to a journey where students, to invoke the late Ted Sizer, ‘learn to use their minds well.’ ” In practice, this requires more student-centered inquiry, research, problem solving, disciplinary thinking, discussion, presentations, and taking informed civic action. by Matt Doran Anchor charts help make thinking visible by identifying key content, strategies, and processes during the learning process. Posting anchor charts (and/or distributing reference sheets) provides a scaffold tool for students as they read, discuss, and write about ideas in class. The four new anchor charts below are designed for use in the social studies classroom to support students in historical event analysis, close reading of primary and secondary sources, classroom discussions, and evidence-based writing. Download the posters here:

The posters can be printed on 8 1/2 x 11, 8 x 14 or scaled all the way up 24 x 60 on a poster printer. by Matt Doran

For a recent professional development workshop, I set out to create learning modules that would introduce middle school teachers to some interactive online games and simulations. Finding quality interactives that met my search parameters proved be a challenging task, but one that resulted in a good collection of digital interactives. Search Parameters First, the interactives needed to align with one of five themes based on our middle school social studies standards (created as Google Classroom “breakouts” for the PD experience): American History/Civics, Ancient History, Economics, Medieval/Early Modern History, and World Geography. Second, to align with the pedagogical emphasis of the PD experience, these interactives also needed to go beyond trivia or review games. They needed to emphasize process standards in the areas of historical or spatial thinking and decision-making skills. Our state content standards are mostly conceptual in nature (cause-and-effect, patterns, processes)-- so most military simulation games really didn’t fit the parameters well. Third, the interactives needed to be web-based (not downloaded software) and free of charge. Since we are a chromebook district, I did not worry about mobile capability with iOS, so flash games were fair game. Results After searching with a variety of keywords and using many online lists (and finding many broken links), I came up with the collection below, organized by theme. (Note: the quality of these interactives varies greatly, but I avoided a rating system for now.) American History/Civics

Ancient History

Economics

Medieval/Early Modern History

World Geography

Questions for Reflection and Discussion (Feel free to comment below) 1. What do you see as the benefits of online simulation activities? 2. How could you incorporate these activities into classroom instruction? (even if you do not have 1:1 devices) by Matt Doran

This year’s election was a keen reminder to all of us in the civic education community of the importance of teaching students how to evaluate online information. Fake news--in the form of click bait, political propaganda, falsified images, and spurious memes--permeates social media feeds today. Craig Silverman of Buzzfeed highlights the problem in the video linked here. How do we teach students (and citizens) to evaluate online information in order to make informed decisions? The Stanford History Education Group (SHEG) and the News Literacy Project (NLP) are both taking up the worthy task helping students evaluate online information. SHEG has recently developed and administered assessment tasks for civic online reasoning--the ways in which students search for, assess, and evaluate online information. Civic online reasoning consists of three core competencies: 1) Who is behind the information? 2) What is the evidence? and 3) What do other sources say? In increasing order of complexity, here are three performance tasks SHEG developed to assess students' use of online information.

The News Literacy Project has developed a suite of teaching tools and elearning modules for evaluating online information:

We have much work to do in the field of civic education in order to help our students become informed participatory citizens. As the methods of receiving and processing information change in the 21st century, our teaching approaches must keep up. SHEG’s civic online reasoning and NLP’s news literacy tools can help us accomplish this task. by Matt Doran The emphasis on historical thinking and critical textual analysis has been one of the most positive developments in the field of social studies education in recent years. Reading Like a Historian, Document-Based Questions, Common Core Literacy in History, the C3 Framework, and the new AP U.S. History all place these skills at the forefront of effective history/social science pedagogy. While these have been important skills within the discipline for some time, they are increasingly being recognized as interdisciplinary skills as well. Accordingly, the myth that social studies must be a “backburner” subject can be thoroughly debunked.

At the 2016 National Council for the Social Studies Conference, I was excited to see how the new SAT is assessing and reporting on students' abilities to critically analyze history and social science related texts on the Reading, Writing & Language, and Math tests. The texts are drawn from a category of “U.S. Founding Documents and Texts from the Great Global Conversation.” These include, “engaging, often historically and culturally important, works grappling with the issues at the heart of civic and political life.” Students need to be able to: read historical sources, cite evidence to support arguments, and interpret informational social science graphics. On the Math test, questions involving problem solving & data analysis can assess students’ understanding of how to draw a reliable conclusion to a social studies research question. Six full-length practice tests for the SAT can be accessed online here: https://collegereadiness.collegeboard.org/sat/practice/full-length-practice-tests. To group the questions related to history/social studies, download the “Scoring Your SAT Practice Test” for each test and scroll to the section labeled “Get Cross-Test Scores” (green). The inclusion of history/social studies textual analysis on the new SAT also demonstrates the increasing alignment of College Board initiatives. College Board recommends using the practice DBQs and Short-Answer Questions from the new AP U.S. History as SAT preparation tools. This is another positive step in the direction of developing the critically-minded students and citizens we need for the 21st century world.

by Matt Doran Updated infographic with new content literacy tools 2/2/19

Skills: What do we want students to be able to do? Critically analyze texts, research to deepen understanding, and construct evidence-based arguments.

Literacy across the curriculum goals can be summarized in three learning targets: 1. Read Closely for Textual Details

2. Research to Deepen Understanding

3. Construct Evidence-Based Arguments

Here are 13 web tools and apps that support one or more of these targets. All of these tools are free at some level; some also offer upgraded premium versions. |

Blog Categories

All

Blog Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

3/23/2020

0 Comments