|

By Matt Doran

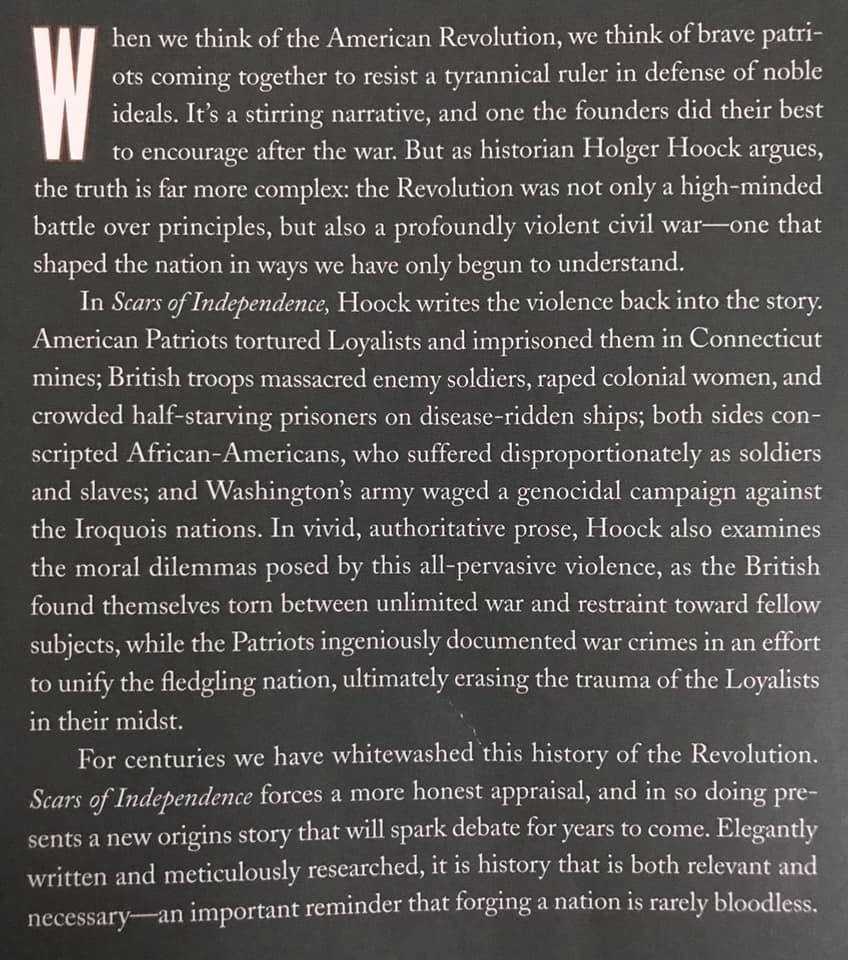

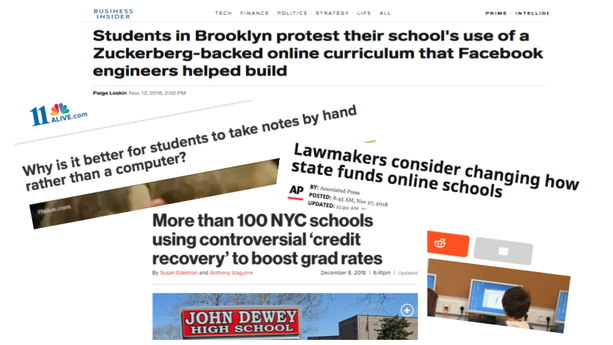

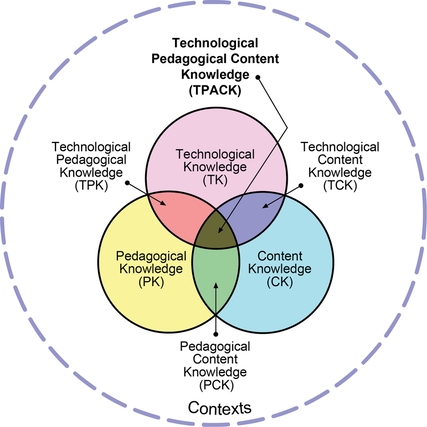

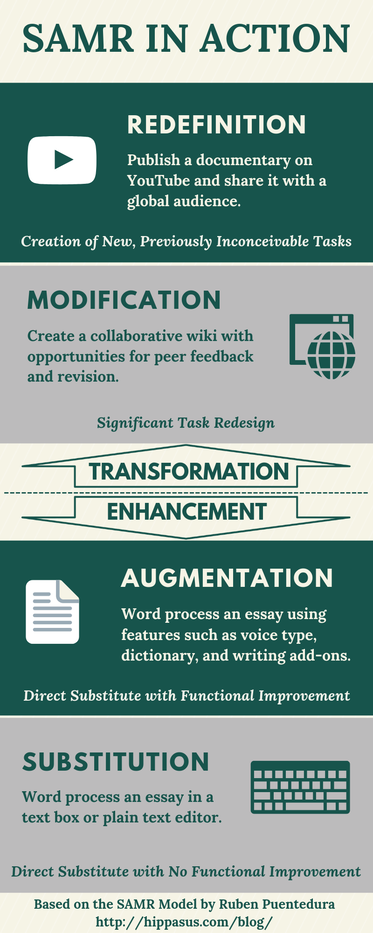

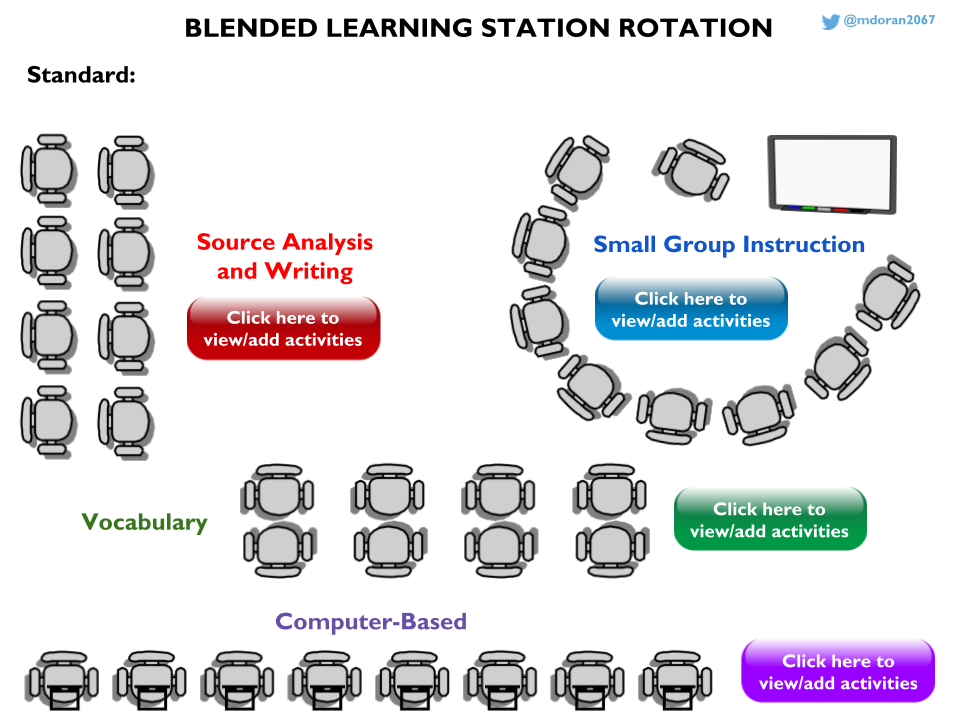

Especially on patriotic holidays, our propensity is to sanctify the causes of our wars. But clear historical analysis compels a more complex and nuanced narrative. The back cover of Scars of Independence: America's Violent Birth by Holger Hoock gives us pause for reflection and analysis. by Matt Doran I have recently started using the graphic below as a hook activity in my Introduction to Blended Learning workshops. Participants are quick to note that, after 20+ years of online learning, we still have yet to achieve consensus on how to do it well. Sociologists refer this phenomenon as cultural lag--when technological advancements occur faster than the rules and norms of society that go along with those advancements. Unfortunately, two decades of haphazard technology integration efforts make it difficult to forge new paradigms in the face of long-standing practices. There are, however, a number of models and principles that can guide our shift. I have summarized these principles in four points below, with an overarching emphasis on placing learning first. 1. Emphasize Effectiveness over Efficiency The primary motivation for technology integration is not doing school more efficiently, but doing education more effectively. To be sure, there are a myriad of technology tools that allow schools and teachers to use their time more efficiently, and produce more actionable data. We should employ these tools to their fullest extent. There are, however, other ways in which emphasizing efficiency can be counterproductive. Online classes with teacher caseloads of 200+ and credit recovery labs with 30+ students working on different courses/subjects monitored by one teacher may be more efficient ways to do school. But neither practice is supported by the plethora of research on the importance of foundational direct/explicit instruction and meaningful teacher to student discussion and feedback. By contrast, technology integration through the lens of educational effectiveness places technology as a means to an end. Using the TPACK (Technological, Pedagogical, And Content Knowledge) Framework, we can establish pedagogical content goals, and leverage technology to achieve the ends. We begin by aligning our content goals with standards, then determine best practices to meet them. Layering in the technology, we ask: how can technology help meet these goals? The ISTE Standards for Students help envision technology’s role in cultivating 21st century learners. These standards call for students to be empowered learners, digital citizens, knowledge constructors, innovative designers, computational thinkers, creative communicators, and global collaborators. Again, technology, effectively leveraged, serves as a means to developing these dispositions. 2. Prioritize Pedagogy over Paperless Moving lessons from paper to paperless provides little impact without transforming our pedagogy. Paperless is great, but so is paper. When to use either is a contextual decision--neither medium is inherently better. Technology presents us with ample opportunities to transform pedagogy from teacher-centered to student-centered classrooms. The SAMR (Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, and Redefinition) Model provides a framework for transformative student-centered pedagogy. In Substitution, technology acts a direction substitution, with no functional change. Augmentation offers tool substitution with some functional improvement. Both of these uses provide lesson enhancement. Modification and Redefinition, by contrast, transform learning. Modification allows for significant task redesign, while Redefinition allows for the creation of previously inconceivable tasks. There are good reasons to assign tasks at any level of SAMR. But our highest aims should be the transformation of learning. 3. Build Better Lessons through Blended Learning Technology is most effective when it is part of a seamlessly integrated syllabus of face-to-face and online activities, with both types of activities building toward common pedagogical content goals. Blended Learning provides for increased student agency, with greater student control over time, place, path/and or pace of learning. Blended Learning restructures the classroom, with time for in-classroom collaboration and small group activities. A Blended Learning approach also helps cultivate a community of learners by using online tools to foster cognitive presence (critical thinking), teacher presence (instruction and feedback), and social presence (student-to-student interaction). Station rotation is a popular model of Blended Learning that works well in non-1:1 classrooms. In an elementary classroom, rotations may occur within the literacy block, or may include multiple subject areas in a day. In a secondary classroom, stations typically last several class periods with 1-2 stations completed in a day. 4. Require Rigor, Relevance, and Relationships

We should have the same expectations of our software that we have of our face-to-face instruction: deep alignment to standards, cultivation of critical thinking, high level engagement, and opportunities for building communities of learners. We should avoid Computer Assisted Instruction (CAI) programs that offer little more than textbooks pasted into a browser, accompanied by low-level comprehension questions. Too often, these programs use only keywords to determine standards-alignment, with little regard for the cognitive demands or requisite process standards. Reasons other than high-quality pedagogy are often the decisive factors in CAI adoption decisions. Ease of use, system compatibility, breadth of coverage (it can be used for all courses) and past practices must take a back seat to rigor and relevance. A better approach is to look for the best digital products (commercial, open-source, and locally-developed) within each content area, and customize them with a robust Learning Management System. An LMS also serves as a hub for building an online community, strengthening the relationships that are created through face-to-face discussions in the classroom. Technology will continue to rapidly advance and change our schools. Our understanding of best practices in technology must continue to grow as well, along with our abilities to effectively employ these practices. But when we keep a learning first mindset, we recognize that the principles that guide us are more important the gadgets among us. by Matt Doran

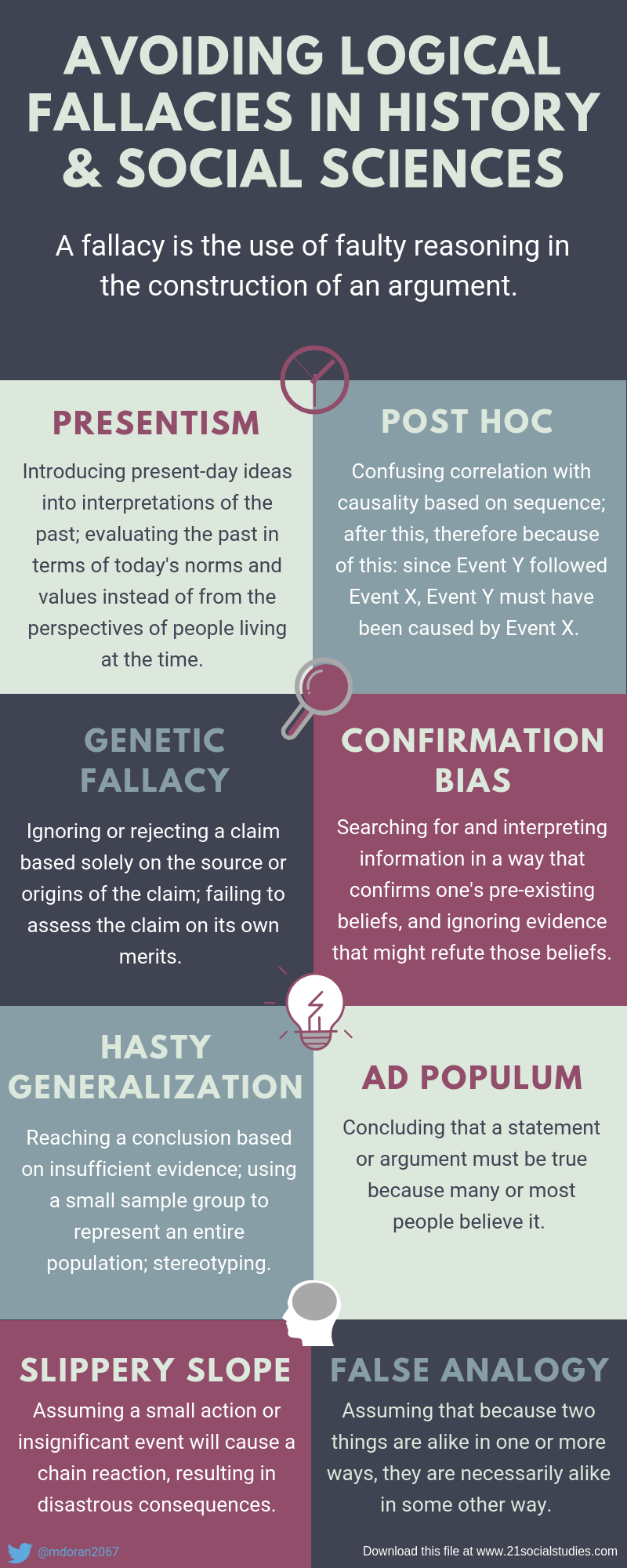

This month we began year three of our middle school professional development program, with an emphasis on pedagogical content knowledge. We are focusing our discussions on creating and implementing a vision for social studies in alignment with the C3 Framework. Since social studies is not a state-tested subject in Ohio middle schools, there is often a perception that it is the least important of the core subjects. Balderdash. The opposite is true: Social studies is too important to force into the constraints of state testing. Free from the yoke of testing, middle school social studies teachers have the freedom and flexibility to execute a vision of social studies education that aligns with both the original intent of social studies and its vital purpose in 21st century democracies. The skills, reasoning capacities, and civic dispositions social studies cultivates cannot be effectively captured through a standardized test. The centrality of social studies among the school subjects lies not in its place within the cesspool of corporate testing and sham accountability systems, but in its instrumental purpose in modern democracies. As conceived by the Report of the Social Studies Committee in 1916, social studies is a discipline designed to actualize a Deweyan vision of pragmatism in education. Drawing from a wide-range of disciplines in the humanities and social sciences, social studies aims to tap into students’ interests and use inquiry-learning to solve real-world problems. Its purpose is explicitly instrumental: to improve society. Having emerged in the Progressive Era, the creation of the social studies in school curricula was part of a broader response to the ills and excesses of Gilded Age industrial capitalism. The Progressive Era ushered in democratic reforms in states (referendum, initiative, recall) and the U.S. Constitution (17th and 19th amendments). Laws were passed to safeguard food production and the environment, limit the power of corporate trusts and monopolies, and establish compulsory public education. In the decades since the Progressive Era, historians and social scientists of the various disciplines that make-up social studies have defined thinking skills central to the disciplines. Such skills include conducting original research, contextualizing historical sources, creating and analyzing data sets, evaluating sources, supporting arguments with evidence, and unpacking cause-and-effect relationships. Many scholars today argue that we are living in a Second Gilded Age, defined by social and economic inequality and political corruption. Even if one doesn’t agree with this characterization of our present times, it is difficult to imagine a case being made against the critical importance of social studies in the 21st century. Do we need increased civic engagement, better civil discourse, more cultural awareness, heightened concern for social justice, greater discernment in evaluating the credibility of information, creative cross-disciplinary solutions to real-world problems, and sharper ethical thinking skills? If so, then we need more social studies, not less. As Natalie Wexler has written in a recent Forbes article, “We know that only a minority of students will end up working in STEM fields. But virtually all will be expected to exercise their rights and responsibilities as citizens of a democracy.” With great freedom comes great responsibility. As social studies teachers, we bear the responsibilities of communicating the importance of our vision to the broader community, and designing and aligning our curriculum to meet this instrumental purpose. We cannot decry state testing on the one hand, while continuing to pack our non-tested courses with a superfluity of Googleable names, dates, and facts on the other. In Why Learn History, When It’s Already on Your Phone, Sam Wineburg describes the ongoing work of the Stanford History Education Group to “change history class from a forced march through an all-knowing textbook to a journey where students, to invoke the late Ted Sizer, ‘learn to use their minds well.’ ” In practice, this requires more student-centered inquiry, research, problem solving, disciplinary thinking, discussion, presentations, and taking informed civic action. by Matt Doran Anchor charts help make thinking visible by identifying key content, strategies, and processes during the learning process. Posting anchor charts (and/or distributing reference sheets) provides a scaffold tool for students as they read, discuss, and write about ideas in class. The four new anchor charts below are designed for use in the social studies classroom to support students in historical event analysis, close reading of primary and secondary sources, classroom discussions, and evidence-based writing. Download the posters here:

The posters can be printed on 8 1/2 x 11, 8 x 14 or scaled all the way up 24 x 60 on a poster printer.

Here are some summary tweets from a panel discussion on Personalized Learning at the 2018 ISTE Conference.

by Matt Doran

For a recent professional development workshop, I set out to create learning modules that would introduce middle school teachers to some interactive online games and simulations. Finding quality interactives that met my search parameters proved be a challenging task, but one that resulted in a good collection of digital interactives. Search Parameters First, the interactives needed to align with one of five themes based on our middle school social studies standards (created as Google Classroom “breakouts” for the PD experience): American History/Civics, Ancient History, Economics, Medieval/Early Modern History, and World Geography. Second, to align with the pedagogical emphasis of the PD experience, these interactives also needed to go beyond trivia or review games. They needed to emphasize process standards in the areas of historical or spatial thinking and decision-making skills. Our state content standards are mostly conceptual in nature (cause-and-effect, patterns, processes)-- so most military simulation games really didn’t fit the parameters well. Third, the interactives needed to be web-based (not downloaded software) and free of charge. Since we are a chromebook district, I did not worry about mobile capability with iOS, so flash games were fair game. Results After searching with a variety of keywords and using many online lists (and finding many broken links), I came up with the collection below, organized by theme. (Note: the quality of these interactives varies greatly, but I avoided a rating system for now.) American History/Civics

Ancient History

Economics

Medieval/Early Modern History

World Geography

Questions for Reflection and Discussion (Feel free to comment below) 1. What do you see as the benefits of online simulation activities? 2. How could you incorporate these activities into classroom instruction? (even if you do not have 1:1 devices)

by Matt Doran

John Hattie's meta-meta analysis on visible learning demonstrates the impact of instructional practices on student achievement. Teachers and students can use Google Apps to make these practices more effective. The infographic below highlights some of the top influences on student achievement along with their effect size, and suggested uses of G Suite for implementation. 4/14/2017 G Suite for Disciplinary thinking

by Matt Doran

Google Apps include powerful tools for developing student-centered classrooms and 21st century learning. The infographic below highlights 10 strategies for using G Suite to cultivate disciplinary thinking and skills. by Matt Doran

This year’s election was a keen reminder to all of us in the civic education community of the importance of teaching students how to evaluate online information. Fake news--in the form of click bait, political propaganda, falsified images, and spurious memes--permeates social media feeds today. Craig Silverman of Buzzfeed highlights the problem in the video linked here. How do we teach students (and citizens) to evaluate online information in order to make informed decisions? The Stanford History Education Group (SHEG) and the News Literacy Project (NLP) are both taking up the worthy task helping students evaluate online information. SHEG has recently developed and administered assessment tasks for civic online reasoning--the ways in which students search for, assess, and evaluate online information. Civic online reasoning consists of three core competencies: 1) Who is behind the information? 2) What is the evidence? and 3) What do other sources say? In increasing order of complexity, here are three performance tasks SHEG developed to assess students' use of online information.

The News Literacy Project has developed a suite of teaching tools and elearning modules for evaluating online information:

We have much work to do in the field of civic education in order to help our students become informed participatory citizens. As the methods of receiving and processing information change in the 21st century, our teaching approaches must keep up. SHEG’s civic online reasoning and NLP’s news literacy tools can help us accomplish this task. by Matt Doran The emphasis on historical thinking and critical textual analysis has been one of the most positive developments in the field of social studies education in recent years. Reading Like a Historian, Document-Based Questions, Common Core Literacy in History, the C3 Framework, and the new AP U.S. History all place these skills at the forefront of effective history/social science pedagogy. While these have been important skills within the discipline for some time, they are increasingly being recognized as interdisciplinary skills as well. Accordingly, the myth that social studies must be a “backburner” subject can be thoroughly debunked.

At the 2016 National Council for the Social Studies Conference, I was excited to see how the new SAT is assessing and reporting on students' abilities to critically analyze history and social science related texts on the Reading, Writing & Language, and Math tests. The texts are drawn from a category of “U.S. Founding Documents and Texts from the Great Global Conversation.” These include, “engaging, often historically and culturally important, works grappling with the issues at the heart of civic and political life.” Students need to be able to: read historical sources, cite evidence to support arguments, and interpret informational social science graphics. On the Math test, questions involving problem solving & data analysis can assess students’ understanding of how to draw a reliable conclusion to a social studies research question. Six full-length practice tests for the SAT can be accessed online here: https://collegereadiness.collegeboard.org/sat/practice/full-length-practice-tests. To group the questions related to history/social studies, download the “Scoring Your SAT Practice Test” for each test and scroll to the section labeled “Get Cross-Test Scores” (green). The inclusion of history/social studies textual analysis on the new SAT also demonstrates the increasing alignment of College Board initiatives. College Board recommends using the practice DBQs and Short-Answer Questions from the new AP U.S. History as SAT preparation tools. This is another positive step in the direction of developing the critically-minded students and citizens we need for the 21st century world. |

Blog Categories

All

Blog Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

7/4/2019

0 Comments