Reflections and Collections for the 21st Century Social Studies Classroom

|

by Matt Doran Bags are packed. Guidebook app is marked. It's time for #NCSS16. This will be my seventh NCSS Conference, and I have lost track of how many Washington D.C. trips I have made in the last 10 years. I am a lifelong learner, and I take conferences pretty seriously. They are always energizing experiences. I have a broad range of responsibilities in my job, and even more professional interests, which means I am never at a loss for a relevant session. In fact, my main problem has been deciding among the 4-5 sessions I have marked for each time slot.

A few years ago, a colleague and fellow NCSS conference fan introduced me to the the concept of the conference hashtag and Twitter dicussions in general, both of which have empowered my personal learning network at conferences and beyond. This year I'm hoping to add a few live blog posts to my social media presence. Modeling our expectations for teachers and students, there is no better way to process a day of learning than to immediately write and share out some thoughtful reflections. On a related note, I am also happy to announce a new collorative effort for the Social Studies for the 21st Century blog. My colleagues, Karen Fiedler and Lynda Ray, will be joining the blog (bitmojis and profiles coming soon!). They are two of the finest educators I have worked with in my career--insightful leaders, inspiring role models, and passionate advocates for all children. I am confident that our team effort will far outshine my quite sporadic blogging efforts! Stay tuned!

by Matt Doran Updated infographic with new content literacy tools 2/2/19

Skills: What do we want students to be able to do? Critically analyze texts, research to deepen understanding, and construct evidence-based arguments.

Literacy across the curriculum goals can be summarized in three learning targets: 1. Read Closely for Textual Details

2. Research to Deepen Understanding

3. Construct Evidence-Based Arguments

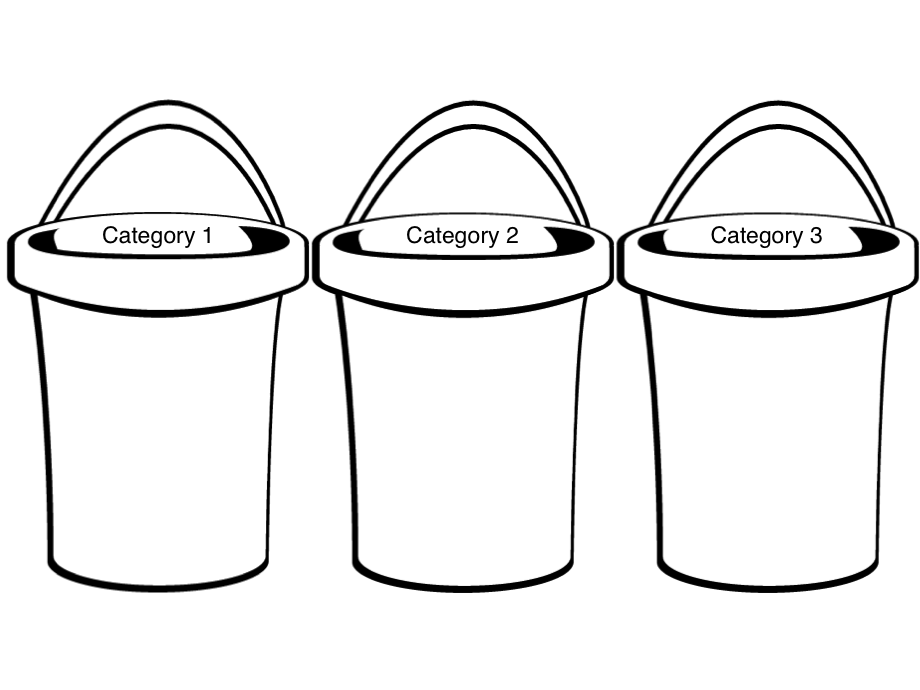

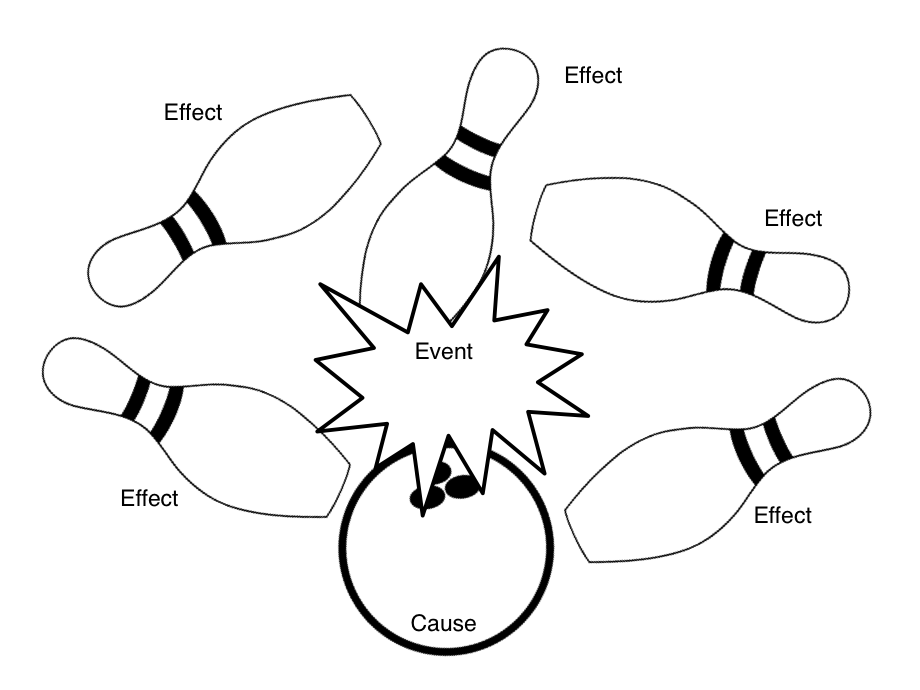

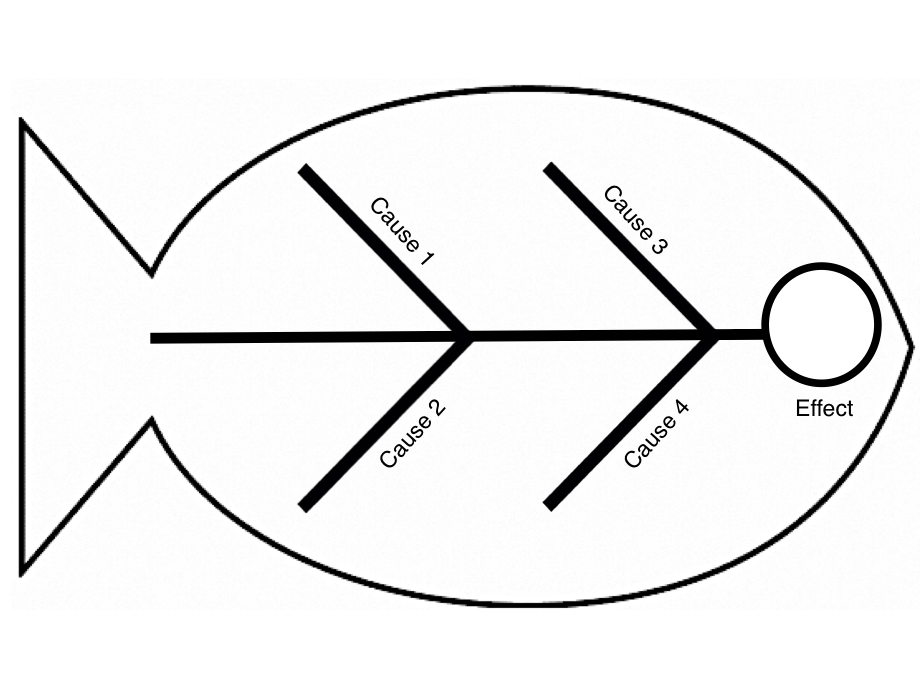

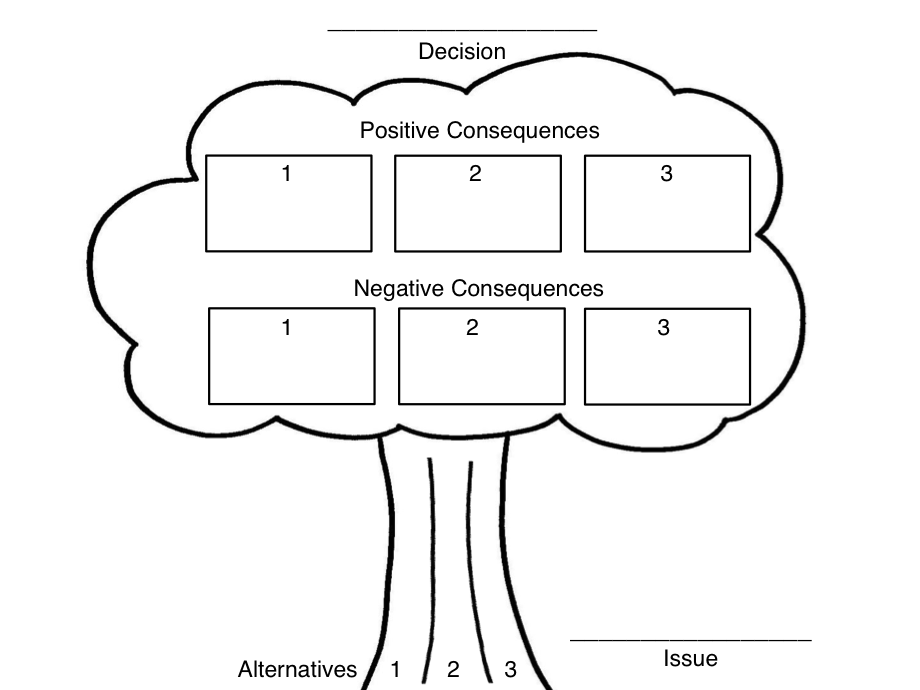

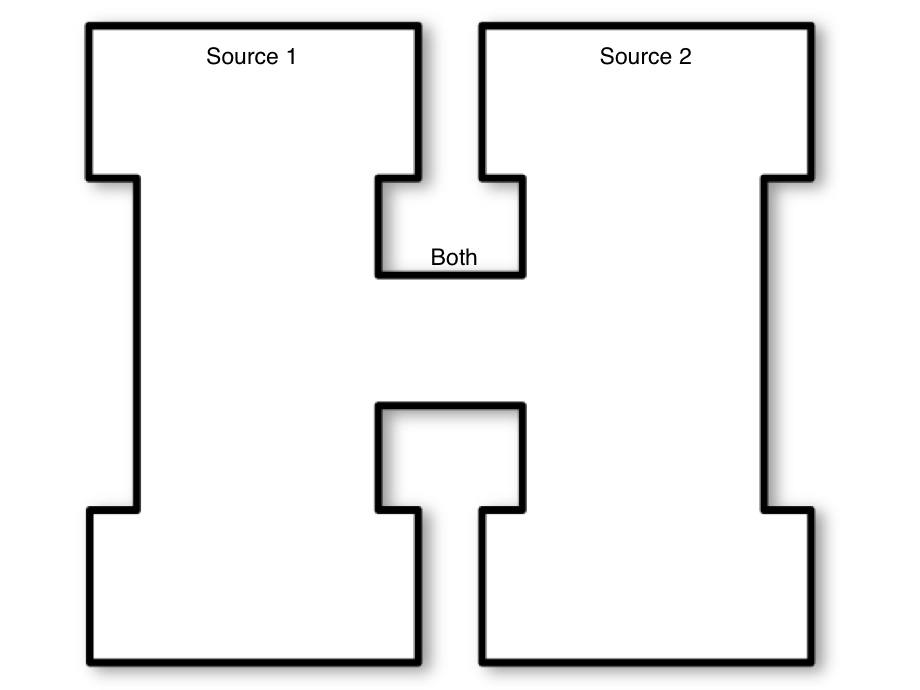

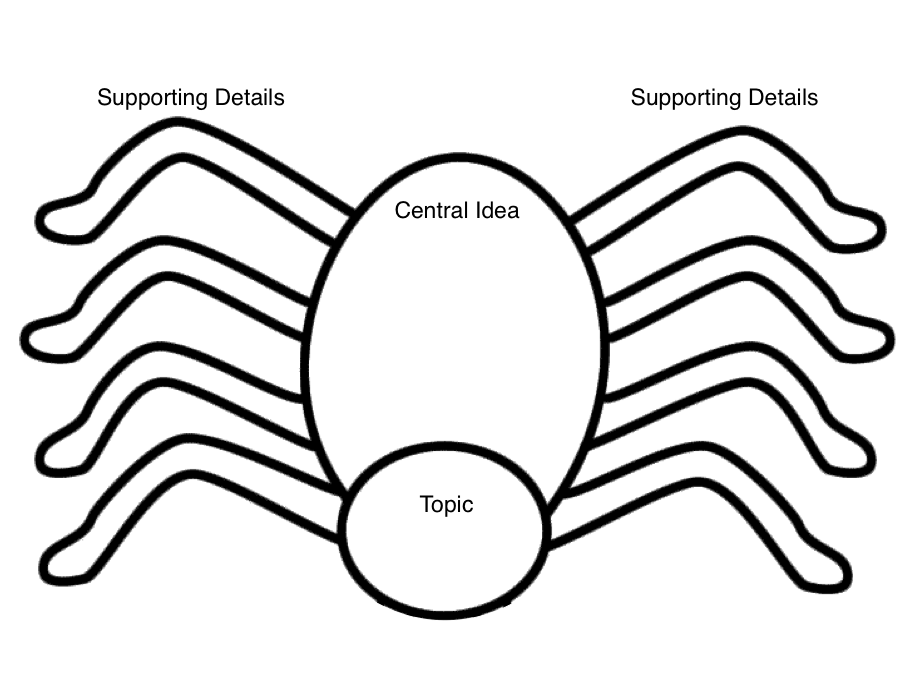

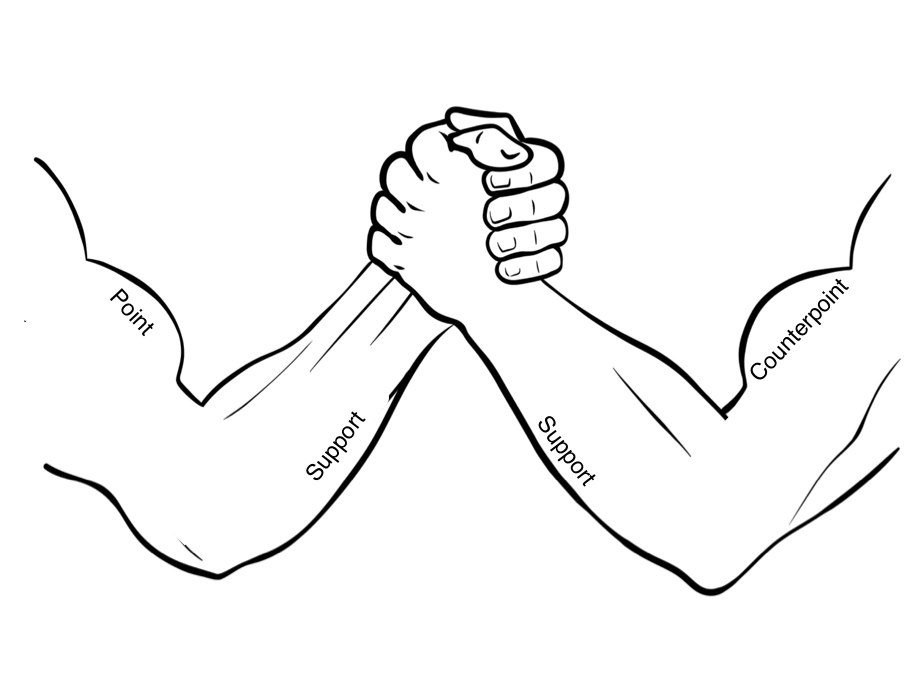

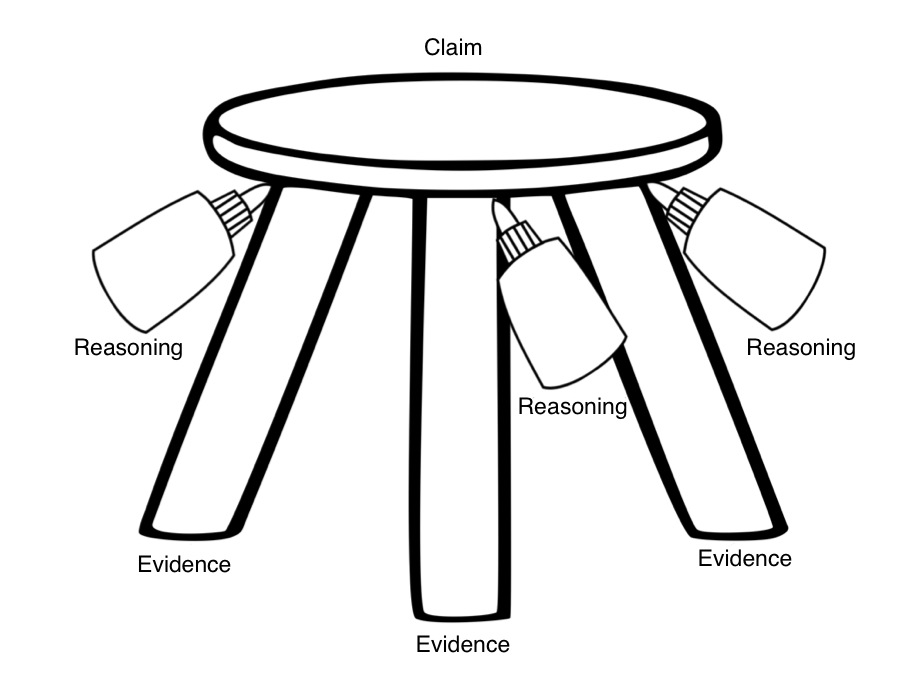

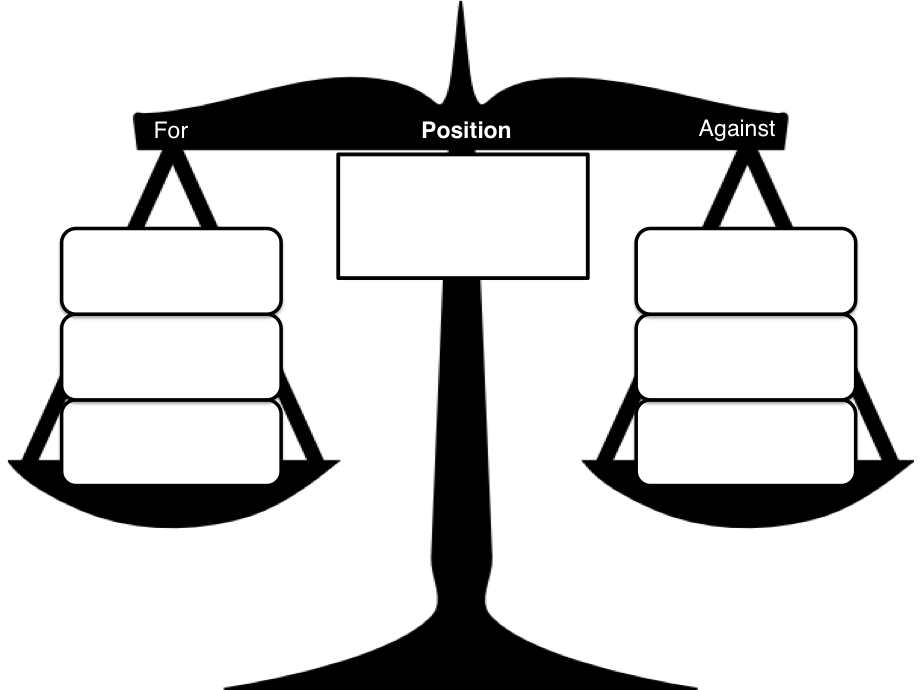

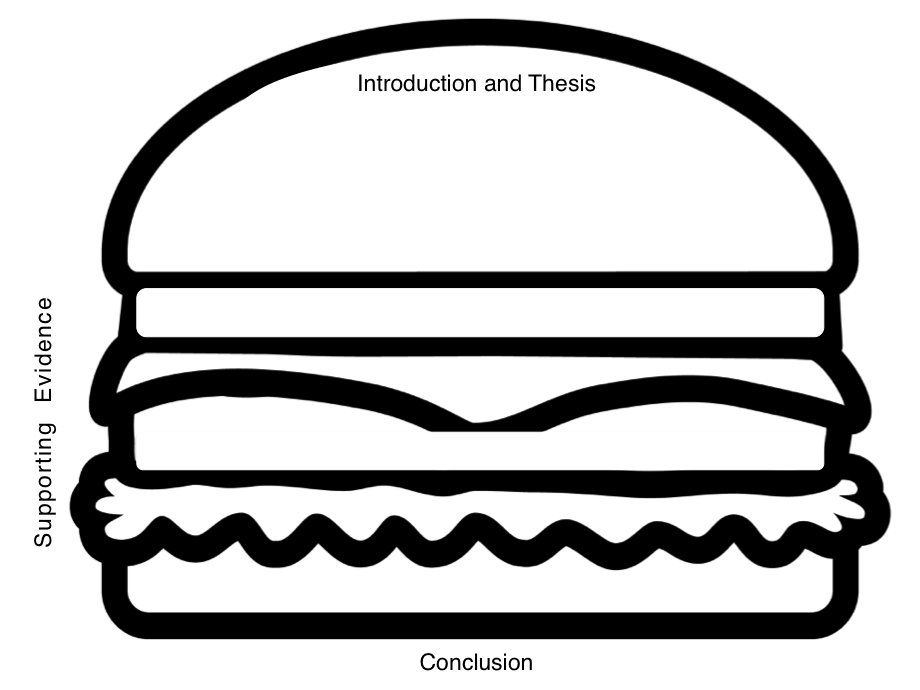

Here are 13 web tools and apps that support one or more of these targets. All of these tools are free at some level; some also offer upgraded premium versions. 4/16/2016 10 Pictographic Organizers for Historical Thinking Skills (Help Yourself to the .PNG Files)by Matt Doran According to dual coding theory, knowledge is stored in both linguistic and non-linguistic (imagery) forms. Pictographic organizers combine the linguistic and non-linguistic modes. They use words, phrases, and sentences along with pictures and symbols to show relationships. The pictographic organizers below provide visual note-taking tools to sharpen historical thinking skills. It is important to note that graphic organizers are only a tool, and must be coupled with inquiry-based pedagogy to maximize effectiveness. Students should be actively engaged in collecting and organizing information in graphic organizers and processing the information from graphic organizers in a variety of ways. Note: Click on the images to download the .png files. The files are designed in 4:3 format for easy integration into presentation software and apps. Classify Information (e.g., social, political, economic factors; types of government) Analyze Cause and Effect Relationships Evaluate Alternative Courses of Action Compare Perspectives in Historical Sources Determine Central Ideas and Supporting Details Make Claims and Counterclaims Support Claims with Evidence and Reasoning Weigh Arguments For and Against a Position Write Persuasive Essays

What are the big ideas, essential questions, and key thinking skills in your social studies classroom? How transferable are they?

"We don't learn in school just to stay in school for the rest of our lives. We have to be able to transfer what we learn in one setting and use it somewhere else. In order to transfer our knowledge we have to be able to learn things in a way that is flexible, that sees the connections between one use of the knowledge and another use of the knowledge.” - Linda Darling-Hammond, Stanford University “The challenge of education is always to ask: What is the least amount of material we can teach really well that will, in turn, make it possible for students to use that knowledge in the widest possible range of situations, not only situations that we can anticipate, but also situations that no one can anticipate. That is, abstractly, the problem of transfer: how can you learn less, and make much more of it?” - Lee Shulman, President of The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching by Matt Doran  Many observers of contemporary American politics believe we have reached the pinnacle of demagoguery and political posturing. True enough, negative campaigning, vitriolic personal attacks, divisive rhetoric, and other forms of incivility, are commonplace today. This conclusion, however, is drawn from a presentist view of the world, rather than from clear historical thinking. Historically speaking, incivility has been a rule rather than an exception in American politics. It is, however, a rule that surely needs to be (and indeed can be) broken. The use of demagoguery—an appeal to people that plays on their emotions and prejudices rather than on their rational side—is as old as politics itself, dating back to Ancient Greece. The American founders understood this propensity. Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist 71, notes, “The republican principle… does not require an unqualified complaisance…to every transient impulse that people may receive from the arts of men who flatter their prejudices to betray their interests.” In Federalist 55, James Madison argues, “In all very numerous assemblies … passion never fails to wrest the sceptre from reason.” In one of first contested presidential elections in 1800, the campaigns of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams engaged in an acerbic war of words. Among other things, Jefferson supporters called Adams a "hideous hermaphroditical character." In turn, Adams supporters branded Jefferson “the son of a half-breed Indian squaw, sired by a Virginia mulatto father,” “an atheist," and “a coward.” The legendary Lincoln-Douglas Senate debates of 1858 were equally vicious, sardonic, and crude. Douglas repeatedly referred to Lincoln’s "Black Republican" party and made frequent use of the N-word. No doubt, hundreds of similar examples could be culled from the archives of twentieth century elections as well. To point out this history is not to suggest that we should lose hope in a better America. To the contrary, knowing this history is the first step in overcoming it. What we need is not a return to some mythical golden age of politics and statesmanship, but to move beyond the vices of our fathers and our own base instincts. In short, we need a new era of reasoned civil discourse grounded in logic, humility, and empathy. The key to the future, therefore, lies in humanities education. As Sam Wineburg argues, “My claim in a nutshell is that history holds the potential, only partly realized, of humanizing us in ways offered by few other areas in the school curriculum. … Each generation must ask itself anew why studying the past is important, and remind itself why history can bring us together rather than—as we have seen most recently—tear us apart.” First, history teaches us how to think. History and civics education must go beyond a curriculum mired in trivia and facts. The answers to the questions we pose should not be Googleable. We must engage students in the compelling, philosophical, and persistent questions that shape humanity. As students pursue answers to these questions, they learn to gather evidence, make inferences, contextualize sources, distinguish facts from value judgments, and identify fallacious reasoning. Second, when we encounter a multiplicity of voices and human experiences, we are humbled by the vast sea of events, information and ideas, and how little we know. Doing history teaches us to avoid hard-and-fast conclusions, but rather to hold suppositions as tentative. The past is gone; only remnants remain. Sometimes new remnants come to light or new ways of looking at old remnants are encouraged, forcing us to rethink our interpretations. Third, history teaches empathy. Empathy is walking in another person’s shoes, the experience of understanding another person's condition from their perspective. As Jason Endocott and Sarah Brooks write, “historical empathy is the process of students’ cognitive and affective engagement with historical figures to better understand and contextualize their lived experiences, decisions, or actions.” The methods we use to teach history are important to cultivating these dispositions. The Structured Academic Controversy (SAC) is a good starting point. This strategy blends the best of evidence-based argumentation with civil discourse. As described on the Teaching American History Clearinghouse website:

The Center for Civic Education’s We the People program is another model program for engaging students in civil discourse. Teams of students prepare oral arguments for a simulated Congressional hearing before a panel of judges, and respond to follow-up questions from the judges. Unlike many recent presidential debates, questions in We the People are deep, philosophical, and provocative. Here is a sample from this year’s national competition:

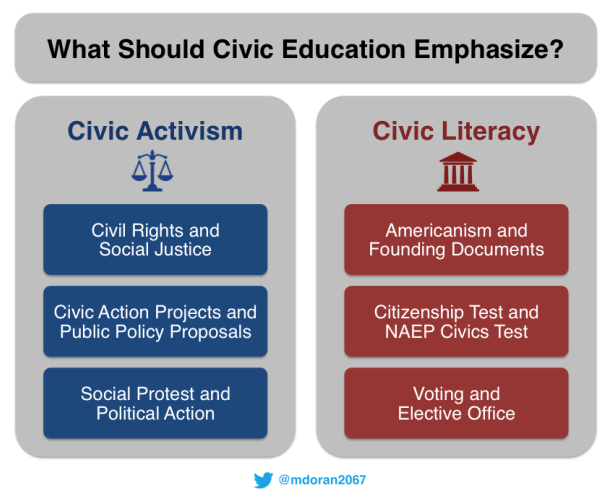

For fostering both historical thinking and historical empathy, Reacting to the Past, an increasingly popular approach used in university history courses, has created a standard for K-12 to follow. The methodology consists of course-long simulations, set in historical context. Students are drawn into the past with assigned roles informed by classic texts. Class discussions and presentations are run by students, with guidance and evaluation from the instructor. Indeed, American politics is, and has been historically, an ugly sphere. But the future can be brighter when the light of history, through the lens of logic, humility and empathy, shines upon it. 12/22/2015 What Should Civic Education Emphasize?by Matt Doran Recent developments have raised questions about what kind of civic education we should have in the United States. Critics of the College Board's new AP US History Framework claimed the framework emphasized negative aspects of American History, and short-changed ideals like American exceptionalism. Others have decried the poor results on the NAEP Civics Test as a clear sign of civic illiteracy. On the other side, many educators viewed the events of Ferguson and the Black Lives Matter movement as opportunities to promote civic activism. Should American History and civics classes emphasize civic activism or civic literacy? Most curricula and classrooms will include some of both, and the two emphases are not mutually exclusive. However, the model below helps us understand these two approaches, and evaluate which way the pendulum may be swinging at the national, state, local, and classroom level. Consider the headlines below. What approach to civic education is emphasized? by Matt Doran

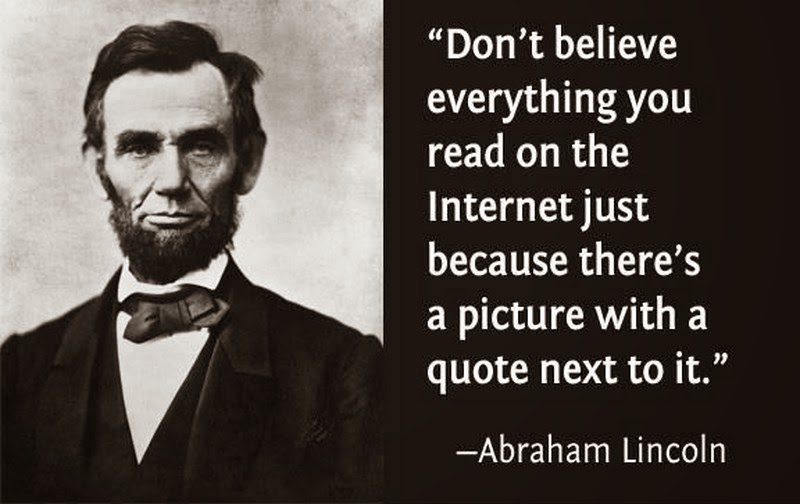

Over the past several weeks, I have been crafting new assessment items around skills standards--credibility of sources, bias, stereotypes, claims, supporting evidence, etc. It strikes me that in the Internet and social media era, we need to update our thinking skills to address Internet legends, viral videos, and social media memes. How do we wade through the multitude of spurious quotes, stories, and claims?

Remember the words of Lincoln... by Matt Doran

Why Study Philosophy? What course would you add to enrich the high school experience for the 21st century? Engineering? Computer Science? Coding? How about philosophy? Yes, philosophy. Learners in the 21st century need the sound reasoning and thinking skills offered by this classical discipline. Even if not offered as a separate course, the study of philosophy woven throughout and across disciplines offers great potential for deepening high school education. The term philosophy means "love of wisdom." As a discipline in the humanities, philosophy offers similar benefits to the traditional subjects of English and history--to deepen and broaden our understanding of the human experience, and in turn, to make us better humans and better citizens. Indeed, many of the essential questions we use to frame English and history courses are philosophical in nature. These questions require us to draw logical deductions, solve ethical dilemmas, and make aesthetic judgments. Philosophy introduces us to the various worldviews that shape human actions across the world. Political philosophy helps us understand the intellectual underpinnings of governments and ideology. These understandings allow us to better engage in meaningful civic dialogue and take informed action. Of course, these are just the philosophical reasons for studying philosophy. Most of us will need practical justifications. (How does this help our students on the test?) Here we can turn to the sub-field of logic. In all disciplines, students are expected to evaluate and construct sound arguments using claims, evidence, and reasoning (warrants). Understanding how to construct logical syllogisms, and avoid logical fallacies, is particularly important in the use of reasoning. Reasoning uses rules of logic to show why the facts and data presented count as evidence. Consider the sampling of standards below drawn from the core academic disciplines to illustrate the importance of logic. English Language Arts (Common Core State Standards)

History (National Center for History in the Schools)

Math (Common Core State Standards Mathematical Processes)

Science (Next Generation Science Standards, Understandings about the Nature of Science)

Resources for Getting Started with Philosophy

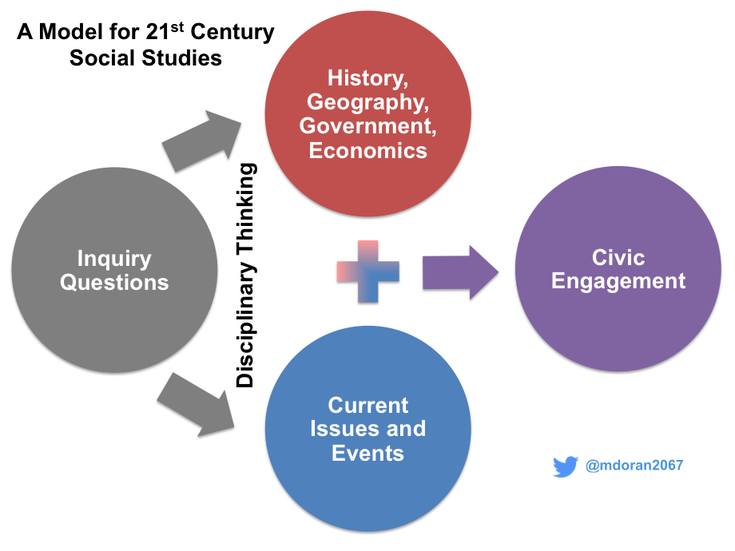

For Further Reading Barry Beyer, "What Philosophy Offers to the Teaching of Thinking." Michael Shammas, "For a Better Society, Teach Philosophy in High Schools." By Matt Doran Skills: What should students be able to do? Apply disciplinary thinking skills to text sets to show the relationship among social studies content, current events, and civic engagement. The use of text sets supports infusion of the Common Core Literacy in History/Social Studies standards, and holds great potential for creating a 21st century social studies classroom. A text set is a collection of readings organized around a common theme or line of inquiry. The anchor text is the focus of a close reading. Supporting texts are connected meaningfully to the anchor text and to each other to deepen student understanding of the anchor text. In social studies, close reading of content texts is not an end in itself, but rather a means to creating successful citizens. In this model, anchor texts can be pulled from rich collections of primary and secondary sources. Supporting texts from current events show the enduring relevance of the themes and questions raised in these readings from history, geography, and government and economics. Applying the tools of disciplinary thinking and common core literacy standards across the text sets prepares students to engage in meaningful civic discourse and take informed action. Here is one example of an inquiry-based text set unit: Course Overarching Essential Question

Unit Compelling Question

Supporting Questions

Text Set Anchor

Supporting

For a complete text lesson, with anticipation guide, adapted readings, and close reading questions, download the resources from this page on Share My Lesson (free account required). by Matt Doran

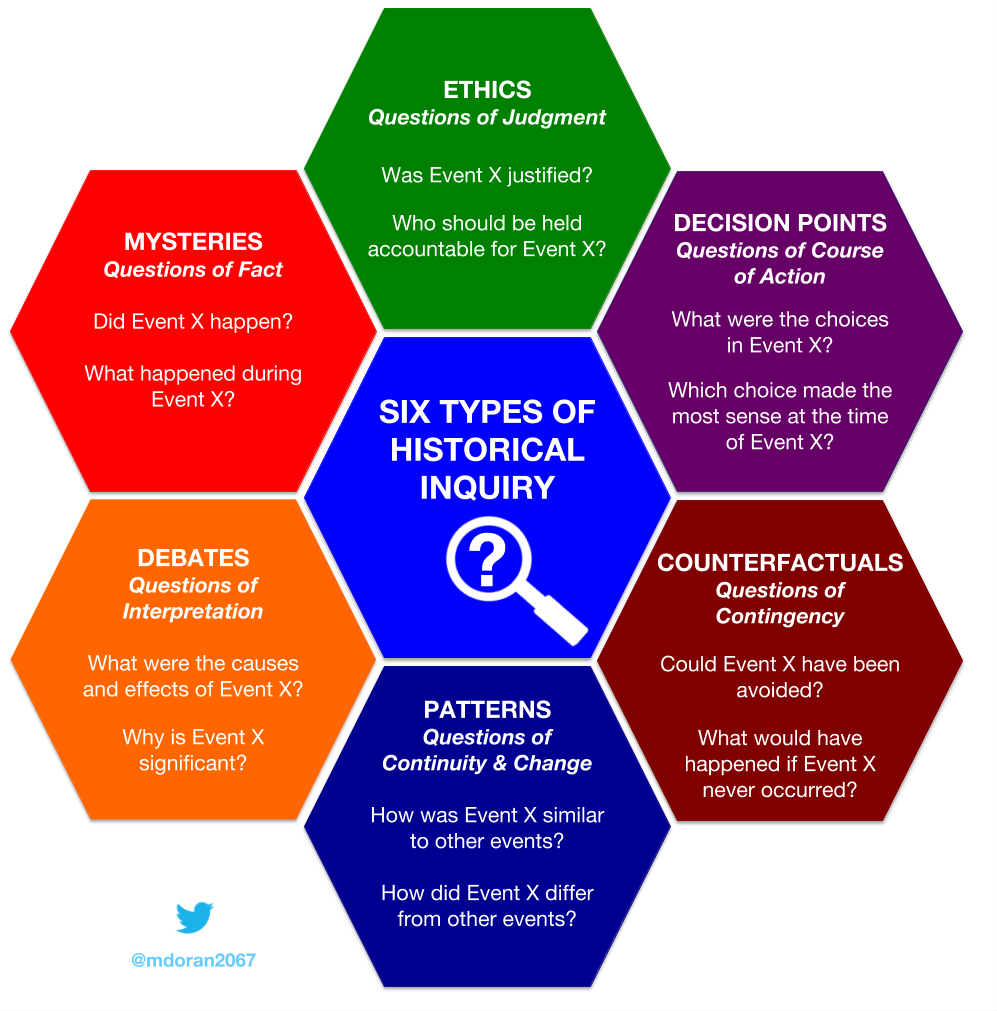

Graphic and source file updated 2/2/19 Inquiry learning is central to history education. What does it mean to do historical inquiry? What types of questions can students investigate? The graphic below highlights six types of historical inquiries. Stay tuned for examples of each type in a folllow-up post. Click here to make a copy of this graphic in Google Drawings. |

Blog Categories

All

Blog Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

12/1/2016

0 Comments